The Vlachs: Metropolis and Diaspora

|

2nd vol. |

After the landmark year 1769, when Moschopolis suffered its first massive collapse, the Vlachs launched their best documented diaspora, from the south northwards. Groups large and small left their ancestral villages along the spine of the Pindos Mountains and moved out into the Balkans and even beyond. Inundating the wider geographical region of Macedonia, they established new settlements in the highlands and colonies in the developing towns. They reached as far as the Rodopi and Balkan Mountains and towns in Bulgaria; they established colonies in towns in Kosovo and Serbia; they crossed the Danube and the Sava to swell the Greek Orthodox communities in the Habsburg Empire and the Danubian Principalities. This account and record of the massive Vlach diaspora clearly shows that Greece itself is the indisputable ‘metropolis’ of the Vlachs.

Mr Koukoudis’s research demolishes numerous myths. He shows, for instance, that the Vlachs have not been merely a marginal group of traditional mountain-dwelling pastoral nomads in the modern era. Although their stockbreeding tradition goes back to the Middle Ages, the pastoral nomads are only one part of the Vlach mosaic. From the early 17th century onwards, when they gradually started to make their demographic presence felt in the Balkans, the Vlachs were not only traditional mountain-dwelling pastoral nomads, but also competent fighters (armatoles and klefts), urban itinerant traders, craftsmen, professionals, and retail merchants, and, by extension, vehicles of economic and intellectual activity. These pages reveal that it is the Vlachs’ recent history that has played the biggest part in defining their identity.

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA

III. The Vlachs of the Northern Pindos: The Vlach villages in the Grevena area

1.3. The Kupatshari

Apart from the known Vlach villages, there is another distinct group of villages in the Grevena area which are of great interest with regard to the former extent of the Vlach settlements. These are the villages of the Kupatshari. Although most of them seem to have been Greek-speaking for many generations, some writers have presented them as having once been Vlach villages or villages with a partially Vlach population, which was gradually assimilated and disappeared together with the Vlach language. Most of the Kupatshar villages lie to the west of Grevena and their names are: Doxaras (Boura), Kyrakli, Elatos (Divrani), Kastro, Anavryta (Vrastino), Kalirahi (Vravonista), Aëtia (Tsouriakas), Messolouri, Prosvoro (Delno or Delvino), Alatopetra (Touzi), Dotsiko (Dousko), Filipaii (Filkli, Firkli), Polyneri (Vodensko), Panorama (Sarganaii, Siarganli), Lavda, Perivolaki (Lipinitsa), Ziakas (Tista), Spilaio, Trikomo (Zalovo), Paroria (Riahovo), Stavros (Paliohori), Kosmati (Kousmatsli in Vlach), Sitaras (Sitovo), Mavranaii (Mavranle), Mavronoros, Kipourio (Tsipourie), Lagadia (Zapado, Zapadaii), Mikrolivado (Labanitsa), and Monahiti (Mounahitlou).[1] It must be noted that the extent and the number of the Kupatshar villages cannot be estimated with any degree of accuracy. They must also include villages to the north and south of Grevena, such as Kalamitsi, Messolakkos (Zgosti), Kalohi, Eleftherohori, Felli, Despotis (Skhinovo), Pigaditsa, Aimilianos (Grindades), Melissi (Plessia), Ayii Theodori, Sitaras, Diakos (Libinovo), and Anthrakia.[2]

Apart from the known Vlach villages, there is another distinct group of villages in the Grevena area which are of great interest with regard to the former extent of the Vlach settlements. These are the villages of the Kupatshari. Although most of them seem to have been Greek-speaking for many generations, some writers have presented them as having once been Vlach villages or villages with a partially Vlach population, which was gradually assimilated and disappeared together with the Vlach language. Most of the Kupatshar villages lie to the west of Grevena and their names are: Doxaras (Boura), Kyrakli, Elatos (Divrani), Kastro, Anavryta (Vrastino), Kalirahi (Vravonista), Aëtia (Tsouriakas), Messolouri, Prosvoro (Delno or Delvino), Alatopetra (Touzi), Dotsiko (Dousko), Filipaii (Filkli, Firkli), Polyneri (Vodensko), Panorama (Sarganaii, Siarganli), Lavda, Perivolaki (Lipinitsa), Ziakas (Tista), Spilaio, Trikomo (Zalovo), Paroria (Riahovo), Stavros (Paliohori), Kosmati (Kousmatsli in Vlach), Sitaras (Sitovo), Mavranaii (Mavranle), Mavronoros, Kipourio (Tsipourie), Lagadia (Zapado, Zapadaii), Mikrolivado (Labanitsa), and Monahiti (Mounahitlou).[1] It must be noted that the extent and the number of the Kupatshar villages cannot be estimated with any degree of accuracy. They must also include villages to the north and south of Grevena, such as Kalamitsi, Messolakkos (Zgosti), Kalohi, Eleftherohori, Felli, Despotis (Skhinovo), Pigaditsa, Aimilianos (Grindades), Melissi (Plessia), Ayii Theodori, Sitaras, Diakos (Libinovo), and Anthrakia.[2]

In the mid-seventeenth century, the inhabitants of many of the villages in the upper Aliakmon valley ― in the areas of Grevena, Anaselitsa or Voio, and Kastoria ― gradually converted to Islam. Among them were a number of Kupatshari, who continued to speak Greek, however, and to observe many of their old Christian customs. The Islamicised Greek-speaking inhabitants of these areas came to be better known as ‘Valaades’. They were also called ‘Foutsides’, while to the Vlachs of the Grevena area they were also known as ‘Vlahoutsi’. According to Greek statistics, in 1923 Anavryta (Vrastino), Kastro, Kyrakali, and Pigaditsa were inhabited exclusively by Moslems (i.e. Valaades), while Elatos (Divrani), Doxaras (Boura), Kalamitsi, Felli, and Melissi (Plessia) were inhabited by Moslem Valaades and Christian Kupatshari. There were also Valaades living in Grevena, as also in other villages to the north and east of the town.[3] It should be noted that the term ‘Valaades’ refers to the Greek-speaking Moslems not only of the Grevena area but also of Anaselitsa. In 1924, despite even their own objections, the last of the Valaades, being Moslems, were forced to leave Greece under the terms of the compulsory exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey. Until then they had been almost entirely Greek-speakers. Many of the descendants of the Valaades of Anaselitsa, now scattered through Turkey and particularly Eastern Thrace (in such towns as Kumburgaz, Büyükçekmece, and Catalca), still speak the Greek dialect of Western Macedonia, which, significantly, they themselves call roumeïka ‘the language of the Romii’.[4] It is worth noting the recent research carried out by Kemal Yalçin, which puts a human face on the fate of 120 or so families from Anavryta and Kastro, who were involved in the exchange of populations. They set sail from Thessaloniki for Izmir, and from there settled en bloc in the village of Honaz near Denizli.[5]

The Kupatshar villages were rather poor farming and pastoral settlements with very few inhabitants, at least in comparison with the nearby Vlach villages; though by the mid-nineteenth century some of them were already practising transhumance after the manner of the Vlach villages.[6] The villages of Dotsiko and Messolouri near Samarina are now deserted in winter, because their inhabitants have adopted a semi-nomadic lifestyle. One of the predominant theories about the etymology of the name ‘Kupatshari’ is that it comes from the Vlach word koupatsiou, which means ‘oak tree’, and specifically the little shoots that grow around the bole. So they may have been called ‘Kupatshari’ because they lived in an area that was once forested with oaks. Weigand, however, asserts that the origin of the name is more probably the Slavonic word kupats, which means ‘digger’ or ‘farmer’ and is more appropriate, since most of the local people were, indeed, farmers.[7]According to Riki van Boeschoten, whatever the correct derivation may be, the term ‘Kupatshari’ seems to carry a somewhat pejorative nuance, because the Vlachs looked down on the people who lived in lower settlements and farmed the land. All the same, the scorn was probably mutual, and nowadays it is considered offensive to call the Kupatshari Vlachs. Apart from any political and historical events and situations that reinforced these feelings (such as the Macedonian Struggle, for instance, or the Axis Occupation), the real, fundamental reasons must be sought in the Vlachs’ and the Kupatshari’s differing roles in the local economy and in the social antagonism which they engendered.[8]

According to Aravandinos, in 1856 most of the Kupatshar villages came under the administrative jurisdiction of the Grevena area, which was known as Vlah Kol ‘the area of the Vlachs’. The name suggests that the Vlachs were in the majority here. He also notes that both Greek and Vlach were spoken in almost all the villages in Vlah Kol. However, in his monograph on the Vlachs, which he wrote in 1865, he does not include the Kupatshar villages among the unquestionably Vlach villages, presumably having realised his mistake.[9] In 1887, Skhinas reports that that there were a total of twenty-four villages in Vlah Kol.[10] When Weigand passed through the local Vlach villages in 1889, he noted the presence of Vlach loanwords in the Greek dialect spoken in the Kupatshar villages and opined that the Kupatshari were linguistically Hellenised Vlachs. This was not his only linguistic error; and he was also wrong when he estimated that the Kupatshari occupied a greater area than they actually did, from Elassona to Kastoria.[11]

Wace and Thompson also noted the process of the Vlachs’ assimilation in Kupatshar villages when they passed through the area in 1911. They described the Kupatshari as linguistically Hellenised or semi-Hellenised Vlachs. The process of assimilation and its advance was, they thought, more or less natural. In a more general review of the assimilation of the Vlach populations in the Pindos, they note that the village way of life and the village economy made it inevitable. They report that the most Hellenised villages (probably meaning both politically and linguistically) were those that had been engaged in agriculture for a long time. In the highland villages that depended on the closely interrelated activities of stockbreeding, trade, and transportation, the Vlachs retained a stronger sense of difference. Even though they had embraced Greek national consciousness, they still regarded themselves as Vlachs. For as long as the system and the organisation of the tselingata persisted, they helped to maintain this sense of difference. But the agricultural Vlach villages ― and some, though certainly not all, of the Kupatshar villages had once been Vlach villages ― tended to deny any Vlach ancestry. In Wace and Thompson’s opinion, the fundamental reason was historical and dated back to an earlier time than any contemporary political propaganda. The agricultural villages had always led a more precarious existence, and the oppression imposed by the conquerors and by their own compatriots had considerably attenuated any notion of independence or sense of difference. Furthermore, intermarriage between Vlachs from the farming villages and speakers of other languages from villages nearby strengthened a trend that had already taken shape. But in the villages where the economy was underpinned by stockbreeding, craft-trades, commerce, and transportation, intermarriage with speakers of other languages was less frequent. This was because the Vlachs in these villages looked down on all farmers, even those who spoke their own language. Farming was far less lucrative than their own occupations. So Vlach parents would not give their daughters in marriage to farmers, and Vlach men rarely married farmers’ daughters, who would not have known how to help them and would have found it hard to conform to the Vlachs’ in many ways unusual way of life.[12] The Vlachs’ sense of difference began to subside and they started to be assimilated as soon as they abandoned their traditional Vlach way of life, settled more permanently in some village in the valleys or the plains, and began to till the land.[13] As long as the phenomenon of cultural division of labour was in force, the sense of difference remained very strong, and this applied equally to Vlachs who were transhumant stockbreeders and those who were engaged in commerce and craft-trades.

Be all that as it may, the Vlach villages near Grevena and certain Kupatshar villages still preserve traditions that confirm that some of the ancestors of the Kupatshari were Vlachs who gradually forgot the Vlach language. According to the traditions, some of the Kupatshari’s ancestors spoke Vlach, and not simply because they lived in close proximity to the local Vlach villages and depended on them economically, but because they were of Vlach descent. Some elderly residents still speak Vlach today in some of the Kupatshar villages, mainly those that had closer connections with the Vlach villages or those in which groups of Vlachs are known to have settled, such as Mikrolivado, Monahiti, Filipaii, and Dotsiko. One indication of the Vlachs’ and the Kupatshari’s shared sense of a close cultural relationship is the fact that they tended to live together and intermarry in the places where they went after leaving their ancestral homes in the nineteenth century, such as the Vlach villages of Mount Vermio (Mikri Sanda) and Mount Askio (Vlasti, Namata).

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA

II. The Vlachs of Zagori and Konitsa

3.2.2. The debate about the former extent of Vlahozagoro

According to one out-dated view, the Vlach villages in Zagori were established in the fifteenth century. Aravandinos, the proponent of this view, includes Negades, Tsepelovo, and Tristeno among them, which allows us to suppose that the Vlach settlements in Zagori covered a much greater area then than now, because these villages seem to have been occupied by Greek-speakers for many generations. What Aravandinos says may be a good starting point for research and debate regarding the former extent and number of the Vlach settlements in Zagori.[1]Lambridis also offers support with the view that the Vlach settlements in Eastern Zagori once extended towards Central and Western Zagori. Villages such as Leptokarya (Liaskovetsi), Kavallari, Negades (Neagan or Neatsiani), Frangades (Frindzi), Tsepelovo, and Skamneli reportedly were once inhabited by Vlachs or at least also by Vlachs. Furthermore, some village names and a number of place-names throughout almost the entire area seem to have a Latin/Vlach root, thus supporting this view. Examples include Skamneli, Vradeto, Koukouli, Baya (now Kipi), Siopotseli (now Dilofo), and Tservari (now Elafotopos).[2] The anthropological medley of Vlach-speakers and Greek-speakers in the villages of, mainly, Central Zagori is also reflected in the Vlach customs which apparently survived there, even after any Vlachs in their populations had been assimilated by the probably more numerous Greek-speakers.[3] Furthermore, when Weigand visited the area at the end of the nineteenth century, he reported that some elderly inhabitants of Tsepelovo, Skamneli, and Dilofo understood Vlach, though the rest were now Greek-speakers. Weigand’s observation must reflect an actual situation, indicative of the assimilation of Vlach-speaking groups among the mainly Greek-speaking inhabitants of Central and Western Zagori.

According to one out-dated view, the Vlach villages in Zagori were established in the fifteenth century. Aravandinos, the proponent of this view, includes Negades, Tsepelovo, and Tristeno among them, which allows us to suppose that the Vlach settlements in Zagori covered a much greater area then than now, because these villages seem to have been occupied by Greek-speakers for many generations. What Aravandinos says may be a good starting point for research and debate regarding the former extent and number of the Vlach settlements in Zagori.[1]Lambridis also offers support with the view that the Vlach settlements in Eastern Zagori once extended towards Central and Western Zagori. Villages such as Leptokarya (Liaskovetsi), Kavallari, Negades (Neagan or Neatsiani), Frangades (Frindzi), Tsepelovo, and Skamneli reportedly were once inhabited by Vlachs or at least also by Vlachs. Furthermore, some village names and a number of place-names throughout almost the entire area seem to have a Latin/Vlach root, thus supporting this view. Examples include Skamneli, Vradeto, Koukouli, Baya (now Kipi), Siopotseli (now Dilofo), and Tservari (now Elafotopos).[2] The anthropological medley of Vlach-speakers and Greek-speakers in the villages of, mainly, Central Zagori is also reflected in the Vlach customs which apparently survived there, even after any Vlachs in their populations had been assimilated by the probably more numerous Greek-speakers.[3] Furthermore, when Weigand visited the area at the end of the nineteenth century, he reported that some elderly inhabitants of Tsepelovo, Skamneli, and Dilofo understood Vlach, though the rest were now Greek-speakers. Weigand’s observation must reflect an actual situation, indicative of the assimilation of Vlach-speaking groups among the mainly Greek-speaking inhabitants of Central and Western Zagori.

Skamneli in Central Zagori is a particularly interesting case. The site of the modern village must originally have been occupied by a small residential nucleus, neither large enough nor significant enough to be mentioned in an Ottoman register of 1564. Later on, possibly at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the inhabitants of the nearby settlements of Katouna, Ayios Yeoryios, Profitis Ilias, Tsepetsi, Kotsinades, and Nouka came and joined this original nucleus. However, this large influx apparently soon led to overpopulation and problems of survival. So in the mid-seventeenth century, some of the inhabitants went off to seek a better life mainly in Moschopolis, and also in Sopiki and Molitsa near Konitsa.[4] The number of people who left for Moschopolis at this time must have been quite large, because they are said to have established a new district there, which was called by the Vlach name of Skamnelitsili (‘the Skamneliots’ district’) and later came to be known as Skamneliki. A much more likely version of the facts is that the Skamneliots moved to Moschopolis not simply because of overpopulation and a desire for better conditions, but mainly because of the general sense of insecurity aroused in the inhabitants of the Zagori villages in the mid-seventeenth century by the frequent predatory raids conducted by bands of Arnauts. According to this version of the story, before the raids the above-mentioned settlements whose inhabitants went to live in Skamneli had, together with Skamneli itself, a population of about 800 families. Possibly after a much more ferocious raid than usual, some of the inhabitants fled to Moschopolis for safety. Moschopolis was chosen as a refuge not only because it offered security as a large, privileged town, but also because the refugees probably had family and professional connections with the inhabitants.[5] After the raids and the departure of the population, the only one of these settlements to survive seems to have been Skamneli itself, where the remaining inhabitants of the surrounding settlements must have congregated. According to yet another version of events, the Vlach contingent of the inhabitants of Skamneli and Tsepelovo originally came from Nouka (which means ‘walnut tree’ in Vlach), which was slightly to the east, in the area of Yiftokambos. This may mean that, before the various settlements which helped to populate Skamneli were abandoned, at least one of them, Nouka, was a Vlach settlement. According to local traditions, the first herdsmen who settled in Vradeto, reportedly around 1616, were from Nouka. Frequent intermarriage between Vlach-speakers and Greek-speakers in Zagori also brought Vlach inhabitants to various villages in Central Zagori.[6]

Following these ekistic and demographic shifts and changes, during the first half of the seventeenth century Skamneli must gradually have ceased to be regarded as a Vlach village, if it ever was (its name suggests that it was indeed). Athanassios Psalidas implies that the inhabitants of Skamneli were originally of Vlach descent when he writes, before 1821, that Vlach had long been forgotten there.[7] The fact that Skamneliots, possibly together with other Zagorites, left to establish a vigorous district in Moschopolis supports the view that the earlier inhabitants of Skamneli were perhaps partially of Vlach origin; though not all those who settled in Moschopolis in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were necessarily of Vlach origin. It must also be noted that the departure of the Skamneliots was part of the more general population drain from the Vlach villages in the Pindos during the seventeenth century. Apart from the Skamneliots, refugees from Metsovo and the surrounding area also arrived in Moschopolis in this period.[8]

Some studies include Leptokarya (Liaskovetsi) and Kavallari in Vlahozagoro, while others do not, but it is not easy to regard them as Vlach villages. However, information does exist that there were once Vlachs among their inhabitants. Leptokarya seems to have grown larger in around 1687, when people from the surrounding little settlements of Ayios Minas, Pades, Romnia, Megalo Dendro, Ayios Yeoryios, Sotiras, and some others further east came and settled there. Earlier records dating to 1732, or more probably to around 1769, state that a number of families from Moschopolis settled there, and were followed by some families from Fourka, who were certainly Vlachs. Those from Moschopolis reportedly brought with them some icons from the Church of St Nicholas in that town. In about the same period, migrants from Moschopolis and Fourka went to Tsepelovo and others from Fourka to Koukouli in Central Zagori.[9] Eventually, the various groups of Vlach-speaking families who added their numbers to the population of settlements in Central Zagori, such as Skamneli, Tsepelovo, and Leptokarya, were gradually assimilated by the much more numerous Greek-speakers; but their presence must explain why these villages are sometimes regarded as Vlach settlements and sometimes not.

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA

I. The Vlachs of the Southern Pindos

The Vlachs of Aspropotamos and Malakassi

7.1 The conditions and the agents of development

The difficult circumstances of the seventeenth century were succeeded by much more favourable conditions for the security and development of almost all the Vlach villges along the Pindos. However, the foundations of this prosperity and developmnent had been laid much earlier, despite the difficulties. Development came gradually and not simultaneously nor to the same degree in all the local Vlach villages. The basis of the economy in many of them was undoubtedly stockbreeding. Furthermore, many of them had been established when various stockbreeding clans and tselingata came together and evolved into more organised pastoral settlements. Simple katuns evolved into organised villages. Taking the cases of the best known and most important of the Vlach villages in the southern Pindos (Metsovo,[1] Syrrako,[2] and Kalarites[3] ) as examples, it is possible to form a more comprehensive idea of how the local Vlachs came to be among the fundamental agents of the economic and cultural renaissance and development of the modern Greek nation.

The difficult circumstances of the seventeenth century were succeeded by much more favourable conditions for the security and development of almost all the Vlach villges along the Pindos. However, the foundations of this prosperity and developmnent had been laid much earlier, despite the difficulties. Development came gradually and not simultaneously nor to the same degree in all the local Vlach villages. The basis of the economy in many of them was undoubtedly stockbreeding. Furthermore, many of them had been established when various stockbreeding clans and tselingata came together and evolved into more organised pastoral settlements. Simple katuns evolved into organised villages. Taking the cases of the best known and most important of the Vlach villages in the southern Pindos (Metsovo,[1] Syrrako,[2] and Kalarites[3] ) as examples, it is possible to form a more comprehensive idea of how the local Vlachs came to be among the fundamental agents of the economic and cultural renaissance and development of the modern Greek nation.

The massive population shifts in the highland communities from the very start of the Ottoman period and the, albeit only relative, security initially provided by self-administration and the armatoliks were the first factors in the development which burgeoned in the eighteenth century. Obviously, the poor mixed agricultural and pastoral economy of the highlands could not sustain the growing population. It was only when more favourable conditions were created for organising and developing stockbreeding that the Vlach villages were able to emerge from their economic standstill. All the same, we must not ignore the fact that almost all the Vlach villages in Malakassi and Aspropotamos kept up a certain degree of agricultural production commensurate with their economic development, which determined whether or not they needed to continue to work the land.[4] The notion that the Vlach communities have always been absolutely and exclusively involved in stockbreeding is a cliché that bears little relation to the facts. The identification of the Vlachs with stockbreeding, particularly its nomadic forms, was more a result of their historical, economic, and cultural development, as also of their adaptation to the environment and the general political circumstances. When one examines the cases of the Vlach villages of both the northern and the southern Pindos, it is easy to see how their economic circumstances and their struggle for survival led the Vlachs more than other groups to develop transhumant and nomadic stockbreeding practices and eventually to be identified so closely with them.

The more vigorous development of nomadic and semi-nomadic stockbreeding resulted in part from the fact that the conditions for the development of farming in the plains were destroyed. When the lowland villages passed into the hands of the spahis, agricultural production gradually declined or even ceased altogether. Vast lowland tracts lay uncultivated and turned into grassland. The depopulation of the plains provided a solution to the problems of overpopulation and survival in the mountains, for the highlanders were now able to develop more organised forms of stockbreeding, which required large winter pastures in the plains. The numbers of their rivals, the Yürüks, who were originally nomadic Turkic stockbreeders, had gradually fallen. At the same time, the Ottoman owners of the lowland pastures welcomed the nomadic and semi-nomadic stockbeeders as a source of extra income, renting them the lowland tracts that were lying idle. The ‘sheep tax’ that flowed into the coffers of the Ottoman state and the local governors also meant that the stockbreeders, whether Vlach or not, were regarded in a more positive light.

It is clear, then, that organised transhumant stockbreeding helped to create more favourable living conditions for the Vlachs. Affluence led to overpopulation, however, and created a need for new forms of economy. One segment of the Vlach population turned to craft-trades based on the products of stockbreeding. The home manufacture of woollen fabrics, which had initially been a matter of survival, became a mass commercial enterprise, and led to standardisation and to the manufacture of clothing. From the splendid rough woollen cloth called skouti they produced their famous kapes, rough sleeveless overcoats much favoured both by shepherds and by sailors. However, the rigid system of the tselingata proved socially and economically stifling for many of their members. The situation was somewhat eased when, having reached an impasse, many of the less privileged members decided to go in for transportation. Since they already possessed large herds of pack-animals, which they used during their seasonal movements between summer and winter pastures and also for supplying their highland villages and keeping the passes open, they decided to operate professionally, transporting the light industrial goods produced in the villages, other commodities, goods, and people through the mountain passes in the Pindos. Some of the muleteers and caravan-drivers (kyradzides) soon opened khans, inns, and wine shops in the economic and administrative centres and also along the Balkan highways as far as Belgrade and Bucharest. At the same time, members of the tselingata gradually turned themselves from transporters into capitalist merchants trading in the woollen articles produced in the local light industrial units, and later evolved into retailers and dealers in all kinds of goods. This was how the caste of the famous itinerant traders (pramateftades) came into being.[5] In the nineteenth century, when cotton seemed to be overtaking wool in terms of marketability and profit, they became cotton merchants and exported it to the West. And they did the same with tobacco at the end of the nineteenth century.

In order to distribute their merchandise and further develop their commercial activities, they journeyed all over the Ottoman Balkans. Many gradually settled down, mainly in towns in Thessaly and Epiros. Small groups settled in the Empire’s large urban centres, even as far afield as Constantinople, or Polea, as the Vlachs call it. In Ioannina (Ialna) and Trikala (Trikolou) they competed with, or even ousted, the older groups of urban merchants.[6] From at least the mid-eighteenth century, the leading families of Aspropotamos, such as the Dimakises of Haliki, the Papapolymerous and the Dimakises or Papadimases of Kastania, and the Hadzipetroses of Neraïdohori, made up a very significant proportion of the Christian gentry of Trikala, occupying or even monopolising the positions of the kocabasis of the town.[7] Merchants from Kalarites traded in skouti from the Vlach villages in both the southern Pindos and the Olympos area.[8] The enterprising families of the wholesale merchants and the kocabasis, as also of the poorer traders and craftsmen who settled in the towns and established family networks, played an active and decisive role in shaping the modern Greek urban class in Epiros, Thessaly, and Macedonia.[9]

A typical case is Ioannina, where Vlach traders and craftsmen mainly from Vlahodzoumerko (Kalarites and Syrrako) and Hora Metsovou settled and became very active in economic, corporate, and communal affairs. The same applies to the Lambros, Tourtouris, Sgouros, and Damiris families from Kalarites, who apparently supplanted older Ioanniot craftsmen in the Ioannina market in the time of Ali Pasha. There were a considerable number of Vlachs in the echelons of Ali’s crowded and much talked-about court, from the humble Metsovite porters who bore his litter on their shoulders to secretaries like Hristodoulos Hadzipetros from Neraïdohori in Aspropotamos (later King Otto’s aide-de-camp), the inspector of the Ioannina market Anastassios Samariniotis, privy councellors like the wealthy merchant Yeoryios Tourtouris from Kalarites, and European-trained doctors like Ioannis Kolettis from Syrrako (later Prime Minister of Greece) and Yeoryios Tsapraslis from Kalarites (who wrote one of the first grammars of the Vlach language). Vlachs from Kalarites, Syrrako, and Metsovo settled en masse in Ioannina and played an active part in revitalising that ruined town after the Greek War of Independence.[10]

Apart from the various craft-trades based on livestock products, other forms of light industry which had disappeared or could not develop in the lowland villages and most of the urban centres survived and developed in the Vlach villages. Apart from considerable mass production of, and trade in, dairy products, some Vlach villages, such as Kalarites and Syrrako, made a name for themselves by developing gold- and silverwork, metalwork, and tailoring.[11] Logging led to the production of wooden implements and other articles and gradually to the development of wood-carving and the production of chancel screens for churches. The fame of the Metsovite wood-carvers and joiners took them as far afield as Philippopolis (Plovdiv). There were also famous coopers, farriers, saddlers, and shoemakers; famous teams of builders and carpenters were set up; tailoring begat the specialised craft of gold embroidery.[12] All these craft-trades provided an outlet for the inhabitants who did not have an active place in the system and castes of the tselingata and the wholesale merchants.

During the eighteenth century, and especially from 1760 onwards, the people of Malakassi and Aspropotamos followed the example of the Moschopolitan Vlachs and took their merchandise in caravans to the commercial towns of Central Europe. They also took advantage of burgeoning Greek shipping to cross the seas and establish commercial firms and colonies in the Mediterranean ports. Merchants from Metsovo, Kalarites, Syrrako, and the kefalohoria of Aspropotamos went as far as Cadiz, Sardinia, Genoa, Leghorn, Naples, Malta, Ancona, Venice, Trieste, and Dubrovnik. They travelled to the Danubian Principalities, Vienna, and Moscow, and settled there. It is revealing that in the membership lists of the Filiki Etairia (1816–21), the various Epirots include a considerable number of Vlach merchants hailing from Metsovo, Milia near Metsovo, Kalarites, Syrrako, Moschopolis, and Ioannina, who were living in Odessa, Moscow, Warsaw, Trieste, Turnu Severin, Bucharest, Galati, Jassy, Reni, Naples, Constantinople, and Alexandria.[13] When Egypt became the new Eldorado in the early nineteenth century, the Vlachs were among the first to play a fundamental part in establishing the Greek colonies there.[14]

They returned to the Vlach villages in the Pindos bringing with them not only economic wealth, but also cultural and intellectual regeneration and development. The Vlach villages were transformed into organised little towns and presented a picture that was quite unprecedented for most of the modern Greek nation that was then taking shape. In Kalarites one could find strong money-lending organisations and find out how the European stock exchanges were faring, and, as Leake tells us, nowhere else did one find such secure credit as in Kalarites. The well-travelled Vlach traders spoke many European languages and were reportedly among the few competent people in the Balkan hinterland with whom the western merchants could work and liaise. French merchants, for instance, established the large warehouses they needed for their merchandise in Metsovo as early as 1719. The Vlach villages had large libraries, well stocked with volumes in both Greek and other languages, a rare phenomenon in those days. Pouqueville was impressed by the orderliness and harmony which reigned in Kalarites, as also by the strict regulations which had been adopted against ostentatious luxury and extravagant dowries and for the support of local products. The Vlach women were no less industrious than the men, and the poorest of them did not object to working even as porters. According to Pouqueville’s estimates, in around 1814 the value of the flocks and herds of the Vlach communities all along the Pindos was about 40,000,000 piastres, while those of Ali Pasha were worth no more than about 2,000,000 piastres.[15]

Passing through the Vlach villages in around 1812–13, Henry Holland noted that the most important Vlach towns were engaged in wool production or in some branch of overland trade and that the inhabitants had the reputation of being among the best craftsmen in Greece. He also observed an air of industry, decorum, and order in the towns, which not only distinguished them from all the other towns in the southern Balkans, but also stood in stark contrast to the wild, rough landscape which surrounded them.[16]

Equally interesting is William Leake’s observation that, though the Vlachs were less sharp-witted than the Greki, they were more steady, prudent, and persevering, though rarely free from internal intrigue, discord, and division.[17]

Pouqueville in his turn notes that,

they are accused of being excessively tight-fisted and obstinate, yet in these rustic ways of theirs we nonetheless discern an unprecedented candour, which is not found in the Levantine character.[18]

Apart from the personal wealth and the highly developed sense of social organisation that characterised most of the Vlach villages, they displayed a general air of communal prosperity. During the eighteenth century, almost all the Vlach villages in the southern Pindos built at least one new church, all of them quite splendid for the time. Those churches, together with the numerous and once rich local monasteries, still stand as irrefutable witnesses to that glorious era.[19] It would probably be superfluous to go into the details of how Greek education developed in the same period in the Vlach kefalohoria in the southern Pindos. Schools like the one at Metsovo were acclaimed centres of the modern Greek Enlightenment, with outstanding teachers of both Vlach and other origin.[20] In view of all this, one might say that the Vlachs contributed even more to the cultural shaping of the modern Greek nation than to the wars and rebellions; and this at a time when the modern Greeks were still seeking and shaping a new Greek identity.

[1] Leake, op. cit., pp. 101-4; Rokkou, V., Υφαντική οικιακή βιοτεχνία, Μέτσοβο 18ος – 20ος αιώνας, Ioannina Centre for Research into Tradition and Culture, Athens 1994.

[2] Krystallis, op. cit.; Moustakis, G., ‘Το Συρράκο και η Πρέβεζα’, Prevezanika Hronika, Nos. 27-28, Jan.–Dec. 1992, pp. 177-214; Karadzenis, N. V., Οι νομάδες κτηνοτρόφοι των Τζουμέρκων, Arta 1991.

[3] Pouqueville, F., Ταξίδι στην Ελλάδα, Ήπειρος, Tolidis, Athens 1994, pp. 287-319; Leake, op. cit., pp. 88-98, 186-90. For more information on Metsovo, Syrrako, and Kalarites see Vakalopoulos, K., Ήπειρος, Kyriakidis Bros., Thessaloniki 1992, pp. 392-7.

[4] For the agricultural economy in the Vlach villages see Kaloussios, D. G., Το Ματσούκι Ιωαννίνων, vol. 1, Ιστορικά, vol. 2, Λαογραφικά, Matsouki and Trikala 1994.

[5] Faltaïts, K., Οι πλανόδιοι Ηπειρώται τεχνίται και η εθνική μας υπόθεσις, Athens 1928.

[6] Vakalopoulos, K., Ήπειρος, Kyriakidis Bros., Thessaloniki 1992, pp. 73-4; Papayeoryiou, Yeoryios, Οι συντεχνίες στα Γιάννενα κατά τον 19ο και τις αρχές του 20ου αιώνα, doctoral thesis, 2nd edition, Institute for the Study of the Ionian and the Adriatic 10, Ioannina 1988, pp. 47, 104-17.

[7] Papanikolaou, N. G., Καστανιά, το χωριό μου, Trikala 1997, pp. 179-89.

[8] Moustakis, op. cit., p. 203.

[9] Pouqueville, op. cit., pp. 307-8; Leake, op. cit., pp. 90-1.

[10] Papayeoryiou, op. cit., pp. 45-7, 51-2, 60, 108, 112, 173-4, 180, 237.

[11] On the goldsmiths and cape-makers of Kalarites and Syrrako, see Papayeoryiou, op. cit., who refers to: Faltaïts, K., ‘Οι πλανόδιοι τεχνίτες στην Ελλάδα’, Ellinika Grammata, vol. 3, No. 1 (25), 16 June 1928; Faltaïts, K., ‘Καποτάδες ― Τερζήδες και Καζάζηδες’, Ellinika Grammata, 1 July 1928; Zora, Popi, Δύο μεγάλοι μάστοροι του ασημιού, Αθανάσιος Τζημούρης – Γεώργιος Διαμαντής Μπάφας, Athens 1972; Konomos, Dinos, Ηπειρώτες στη Ζάκυνθο, Ioannina 1964.

[12] Hadzimihali, Angeliki, ‘Ραφτάδες – χρυσορραπτάδες και καποτάδες’ in the collective work Αφιέρωμα στη μνήμη του Μανόλη Τριανταφυλλίδη, Athens 1960, pp. 445-74.

[13] Aravandinos, P., Περιγραφή της Ηπείρου εις μέρη τρία, part 3, Society for Epirot Studies, Ioannina 1984, pp. 337-9; Vakalopoulos, Ήπειρος, op. cit., pp. 211-16.

[14] The early protagonists included Kyriakos Tassikas, a merchant whose family hailed from the Vlach villages of Aspropotamos, Mihaïl Tositsas, the national benefactor from Metsovo and personal friend and close associate of the Moslem Albanian ruler of Egypt, Mohamed Ali, and the Patriarch of Alexandria, Hierotheos I, who hailed from Klinovos in Aspropotamos and occupied the patriarchal throne from 1825 until his death in 1844.

[15] Pouqueville, op. cit., pp. 307-12; Arseniou, op. cit., pp. 54-9, 70, 77-83, 94-5; Pouqueville, F., Ταξίδι στην Ελλάδα, Στερεά Ελλάδα – Αττική – Κορινθία, Gr. tr.: Mirka Skara, Tolidis Bros., Athens 1995, p. 216. For an account of Pouqueville’s notes on the Vlachs, see Simopoulos, Kyriakos, Ξένοι ταξιδιώτες στην Ελλάδα, 1810-1821, vol. III 2, 4th edition, Athens 1992, pp. 341-9.

[16] Holland, H., Ταξίδι στη Μακεδονία και Θεσσαλία, 1812-1813, Tolidis Bros., Athens 1989, p. 64.

[17] Leake, op. cit., p. 86.

[18] Pouqueville, op. cit., p. 348.

[19] Nimas, T. A., Τρίκαλα, Καλαμπάκα, Μετέωρα, Πίνδος, Χάσια, Kyriakidis Bros., Thessaloniki 1987, pp. 235-79.

[20] Hadzimihali, Angeliki, Οι εν τω Ελληνοσχολείο Μετσόβου διδάξαντες και διδαχθέντες, Ioannina 1939, and in Ipirotika Hronika, 1940; Ziagos, N. G., Τουρκοκρατούμενη Ήπειρος. Τιμαριωτισμός, αστισμός, νεοελληνική αναγέννηση (1648-1820), Athens 1974. For Greek education in Aspropotamos, see Nimas, Theodoros A., Η εκπαίδευση στη Δυτική Θεσσαλία κατά την περίοδο της Τουρκοκρατίας, Kyriakidis Bros., Thessaloniki 1995.

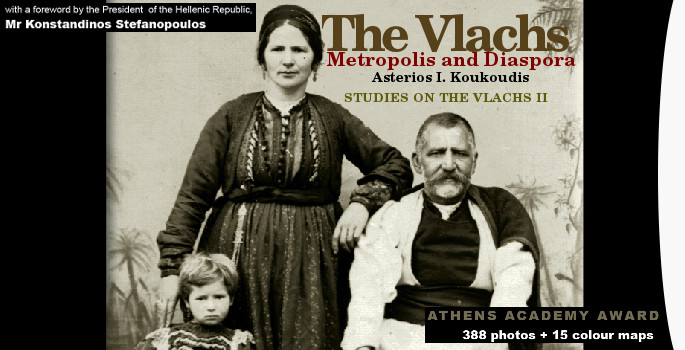

The Vlachs: Metropolis and Diaspora

Studies on the Vlachs - 2nd vol.

hard cover 28x21 cm

516 pages, 15 colored maps

388 old black and white pictures

Zitros Publications, Thessaloniki 2003

Foreword by the Director Yannis Z. Drossos

Maps

Maps

1. The Vlach metropolitan groups in 1769

2. The Vlach villages of the Pindos in 1900

3. The Kupatshari in 1912

4. Vlach villages and settlements in Thessaly (1996)

5. Vlach villages and settlements in western Greece (1996)

6. Vlach villages and settlements in central and southern Albania in 1900

7. The Vlach villages of Roumeli (Pouqueville, 1800–1810)

8. The diaspora of the Moschopolis Vlachs (1769–1830)

9. The Grammousta Vlachs in 1900

10. The Vlachs in the areas of Moschopolis, Grammos, and nw Macedonia in 1900

The Vlachs: Metropolis and Diaspora

Studies on the Vlachs - 2nd vol.

hard cover 28x21 cm

516 pages, 15 colored maps

388 old black and white pictures

Zitros Publications, Thessaloniki 2003

Foreword by the Director Yannis Z. Drossos

Table of contents

Table of contents

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA

I. The Vlachs of the Southern Pindos

The Vlachs of Aspropotamos and Malakassi

1. General

1.1. The Vlach villages of Aspropotamos

1.2. The Vlach villages of Malakassi

‘Hora Metsovou’ and Vlahodzoumerko

2. The Byzantine period: ‘Great Vlachia’

3. References to the Vlach villages in Aspropotamos and Malakassi in the mediaeval and Byzantine period

4. The Ottoman period until the 17th century

5. The exoduses of the 17th century

5.1. The reasons for the exoduses

5.2. To eastern Thessaly, Kissavos, and Pilio

5.3. To Olympos

5.4. To Thessaloniki

5.5. To Moschopolis

6. ‘Hora Metsovou’: the privileges of the Metsovo area

7. The 18th century: economic and cultural development

7.1 The conditions and the agents of development

7.2. Aspects of the remarkable development of the Vlach villages

8. Later exoduses, 1769–1830

8.1. Events associated with the Orlofika

8.2. The dominion of Ali Pasha of Ioannina

8.3. The War of Independence of 1821

9. The Vlach population in Thessaly after incorporation in 1881

Notes I

II. The Vlachs of Zagori and Konitsa

1. General

1.1. Zagori

1.2. The Vlach villages of Konitsa

2. The Byzantine period

3. The Ottoman period from 1430 to 1684

3.1. The general situation

3.2. Demographic and ekistic development and changes between 1430 and 1684

3.2.1. Vlahozagoro

3.2.2. The debate about the former extent of Vlahozagoro

3.2.3. The Vlach villages of Konitsa

4. The Ottoman period from 1684 to 1868

4.1. The ‘Zagori Federation’

4.2. The economy of the Vlach villages of Zagori and Konitsa

4.3. The reasons for the population drain from the Vlach villages of Zagori and Konitsa between 1769 and 1830

4.3.1. The exoduses from Vovoussa

4.3.2. The exoduses from Fourka

5. Emigration in the modern era (second half of the 19th and first half of the 20th century)

Notes II

III. The Vlachs of the Northern Pindos: The Vlach villages in the Grevena area

1. General

1.1. The transhumant Vlach villages

1.2. The permanent Vlach villages

1.3. The Kupatshari

2. The Vlachs’ pastoral nomadism

3. The Byzantine period

4. The Ottoman period I: 15th–17th cent.

4.1. Samarina

4.2. Perivoli

4.3. Avdella

4.4. Smixi

4.5. Krania

5. The Ottoman period II: 18th–19th cent.

5.1. Economic data

6. The exoduses between 1769 and 1830

6.1. The exoduses associated with the collapse of Moschopolis and the Orlofika, 1769–71

6.2. The exoduses in the time of Ali Pasha and the Greek War of Independence, 1788–1830

6.2.1. Exoduses from Samarina

6.2.2. Exoduses from Perivoli

6.2.3. Exoduses from Avdella

6.2.4. Exoduses from Smixi

7. The rebellion of 1854 and the exoduses in the mid-19th century

8. The departure of the Batuts from Samarina (1856–60)

Notes III

IV. The Arvanitovlachs

1. General

2. The Byzantine period

3. The Ottoman period until 1821

4. The Arvanitovlachs in Epiros and Albania after 1821

5. The Arvanitovlachs in Macedonia

6. The Arvanitovlachs in Thessaly

7. The Arvanitovlachs in Roumeli (Mainland Greece)

Notes IV

V. The Vlachs of Moschopolis and the surrounding area

1. General

2. The Byzantine period

2.1. The first references

2.2. Moschopolis and the Arvanitovlachs

2.3. The first settlement

3. The Ottoman period until 1769

3.1. From the Ottoman conquest to 1700

3.2. The glory days, 1700

4. The collapse of Moschopolis and the surrounding Vlach villages

4.1. The circumstances of the first great collapse in 1769

4.2. The events of 1769

4.3. The events of 1788

5. The mass exoduses

5.1. To Western Macedonia

5.2. To Central Macedonia

5.3. To Eastern Macedonia and Eastern Rumelia

5.4. To Fyrom and Kosovo

5.5. To the Pindos, Epiros, and Thessaly

5.6. To Albania

5.7. To the northern Balkans (Serbia) and the Habsburg Empire

6. Moschopolis and the surrounding area after the mass exoduses

Notes V

VI. The Vlachs of Grammos

1. General

2. The Grammoustian Vlachs’ points of departure

2.1. Nikolice

2.2. Arrez

2.3. Darde

2.4. Linotopi

2.5. Ayios Zaharias

2.6. Aetomilitsa

2.7. Kiafa

2.8. Grammousta

2.8.1. From foundation to mass exodus

2.8.2. The mass exoduses from Grammousta

2.8.3. The differentiation of the Grammoustian Vlachs

2.8.4. The diaspora and the colonies of the Grammoustian Vlachs

2.8.5. Foussa and Veterniko

2.8.6. Grammousta after its decline

3. Later Arvanitovlach groups in the Grammos area

Notes VI

VII. The Vlachs in north-western Macedonia

1. General

1.1. Vlach villages and settlements in Western Macedonia

1.2. Vlach villages and settlements in south-western Fyrom

1.3. Vlach villages and settlements in the rest of Fyrom

2. The Byzantine period

3. The Ottoman period

3.1. From the end of the 14th century to c. 1769

3.2. The Vlachs and the Mijaks

3.3. From 1769 to 1912

3.3.1. The exoduses from Moschopolis, the surrounding area, and the area of Grammos to join older Vlach communities and establish new ones

3.3.2. Demographic changes in the time of Ali Pasha of Ioannina and until the mid-19th century

3.3.3. Migratory movements during the 19th century and until 1912

4. The Vlach refugees from Pelagonia after 1912

The Vlachs: Metropolis and Diaspora

Studies on the Vlachs - 2nd vol.

hard cover 28x21 cm

516 pages, 15 colored maps

388 old black and white pictures

Zitros Publications, Thessaloniki 2003

Foreword by the Director Yannis Z. Drossos

Foreword by the Director of the Institute for Defence Analysis Yannis Z. Drossos

In this, the second volume of the four-volume series Studies on the Vlachs, Mr Koukoudis looks at the Vlachs’ ancestral villages and conducts a detailed investigation of their exoduses from those villages and their diaspora throughout the Balkans. It is an investigation that leads to an alternative approach to the Vlach identity. The study of the Vlachs is not the study of a perpetual, discrete linguistic group, but the history itself of the gradual and variable Latinisation and de-Latinisation of the southern Balkans. Shifting populations and diaspora have been constant features of the Vlachs’ history, as has their Latinate speech.

Around the landmark year of 1769, when Moschopolis suffered its first collapse, the Vlachs began their best attested dispersion northwards. Groups both large and small left their ancestral homes along the spine of the Pindos Mountains for the furthermost reaches of the Balkans and even beyond. They inundated Macedonia, creating new villages in the highlands and colonies in the developing towns and cities, and travelling as far as the flanks of the Rodopi and the western Balkan Mountains and the urban centres of Bulgaria. They established communities in towns in Kosovo and Serbia. They crossed the Danube and the Sava and swelled the ranks of the Greek Orthodox communities in the Habsburg Empire and the Danubian Principalities. Mr Koukoudis’s account and record of the dense Vlach diaspora demonstrates that Greece itself is the indisputable ‘metropolis of the Vlachs’.

His research demolishes a number of myths and fictions. It demonstrates that in the modern period the Vlachs were not a marginal group of traditional mountain-dwelling transhumant stockbreeders. Although their roots as stockbreeders go back to the Middle Ages, the nomadic and semi-nomadic herdsmen were only one part of the Vlach mosaic. From the beginning of the seventeenth century, when the Vlachs began gradually making their presence felt in the Balkans, they appeared both as traditional mountain-dwelling transhumant stockbreeders (and by extension as thoroughly capable fighters, armatoles, and klefts) and as urban traders, craftsmen, professionals, and retail merchants (and by extension as agents of economic and intellectual activity). These pages make it clear that it is the Vlachs’ recent past that has been most important and played the biggest part in defining their identity.

Particularly in their ancestral homes in the Pindos and the offshoots of the Pindos, the identical modern history of the Vlach-speakers and Greek-speakers, their joint participation in the armatoliks, the War of Independence of 1821, and the subsequent rebellions throughout the nineteenth century, the Vlachs’ leading role in economic and cultural affairs, their shared development, and their political identification left little scope for disruptive tendencies to take root. Despite the interventions of various outsiders, the Vlachs are still part of the Balkan dimension of Romiosyni and of modern Greece. Ultimately, irrespective of their linguistic identity, the historical evolution of the Vlachs themselves confirms the osmotic relationship between the Greek-speaking and the Vlach-speaking populations and shows how trite and indefensible it is to regard them as a minority.

With the fixing of the borders in the Balkans, from 1912 onwards the vast majority of the Vlachs became Greek citizens, as well as integral members of the modern Greek nation. With very few exceptions (such as the once splendid Moschopolis), almost all the ancestral Vlach homelands along the Pindos are an inseparable part of Greece itself. In contrast to the demographic picture of the Vlachs in the surrounding Balkan countries, in contemporary Greece the ancestral highland villages of all the Vlachs co-exist with a great number of more recent Vlach settlements in the plains and in the urban, economic, and administrative centres from Thrace to Roumeli.

This study, objective and impartial, blazes a new, much smoother trail for research into the Vlachs and helps to develop and consolidate a calm, bona fide scientific debate.

So I am delighted to welcome the second volume in Mr Koukoudis’s four-volume series on behalf of the Institute for Defence Analysis, which supports and encourages the writing of scholarly studies and publications on major issues in modern Greek history.

Yannis Z. Drossos

Page 2 of 2

Subtracts from "The Vlachs: Metropolis and diaspora"

Migratory movements during the 19th century and until 1912

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA VII. The Vlachs in north-western Macedonia 3.3.3. Migratory movements during the 19th century and until 1912 By around the mid-nineteenth century, the network of...

The diaspora and the colonies of the Grammoustian Vlachs

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA VI. The Vlachs of Grammos 2.8.4. The diaspora and the colonies of the Grammoustian Vlachs It is worth mentioning, albeit briefly, the villages and the hut...

Moschopolis, the glory days, 1700–1769

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA V. The Vlachs of Moschopolis and the surrounding area 3.2. Moschopolis, the glory days, 1700–1769 In the eighteenth century, Moschopolis and the local Vlach...

The Arvanitovlachs in Roumeli (Mainland Greece)

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA IV. The Arvanitovlachs 7. The Arvanitovlachs in Roumeli (Mainland Greece) In around 1840, the large Arvanitovlach settlement at Bitsikopoulo was apparently...

The Kupatshari

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA III. The Vlachs of the Northern Pindos: The Vlach villages in the Grevena area 1.3. The Kupatshari Apart from the known Vlach villages, there is another distinct...

The debate about the former extent of Vlahozagoro

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA II. The Vlachs of Zagori and Konitsa 3.2.2. The debate about the former extent of Vlahozagoro According to one out-dated view, the Vlach villages in Zagori were...

The Vlachs of Aspropotamos: The conditions and the agents of development

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA I. The Vlachs of the Southern Pindos The Vlachs of Aspropotamos and Malakassi 7.1 The conditions and the agents of development The difficult circumstances of the...