Studies on the Vlachs

When I used to go to my mother’s village in Roumlouki, I remember how my Grekos grandad, barba-Dziordzi, would ask me: ‘What are you, lad, a Romios or a Vlahos?’. And in Veria, my Vlach grandad, lala-Steryios, would ask me in Vlach: ‘Tse hi tini, Armin ia Grek?’ (What are you, an Aroumanian or a Grekos?). And, anxious not to disappoint either of them, I would give each the answer he wanted to hear. It was years later that I realised that they both wanted me to say the same thing, but each wanted to hear it in his own language.

Subcategories

The Vlachs: Metropolis and Diaspora Article Count: 12

|

2nd vol. |

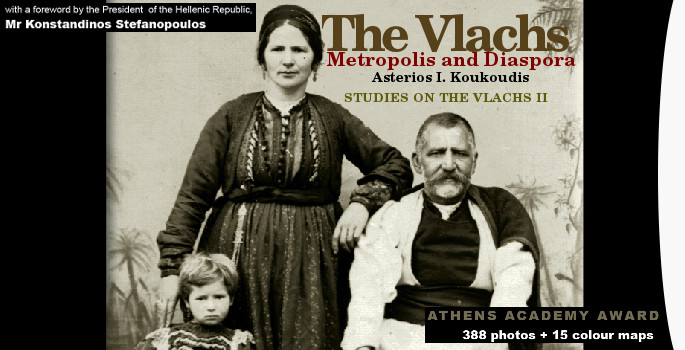

After the landmark year 1769, when Moschopolis suffered its first massive collapse, the Vlachs launched their best documented diaspora, from the south northwards. Groups large and small left their ancestral villages along the spine of the Pindos Mountains and moved out into the Balkans and even beyond. Inundating the wider geographical region of Macedonia, they established new settlements in the highlands and colonies in the developing towns. They reached as far as the Rodopi and Balkan Mountains and towns in Bulgaria; they established colonies in towns in Kosovo and Serbia; they crossed the Danube and the Sava to swell the Greek Orthodox communities in the Habsburg Empire and the Danubian Principalities. This account and record of the massive Vlach diaspora clearly shows that Greece itself is the indisputable ‘metropolis’ of the Vlachs.

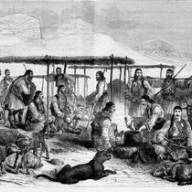

Mr Koukoudis’s research demolishes numerous myths. He shows, for instance, that the Vlachs have not been merely a marginal group of traditional mountain-dwelling pastoral nomads in the modern era. Although their stockbreeding tradition goes back to the Middle Ages, the pastoral nomads are only one part of the Vlach mosaic. From the early 17th century onwards, when they gradually started to make their demographic presence felt in the Balkans, the Vlachs were not only traditional mountain-dwelling pastoral nomads, but also competent fighters (armatoles and klefts), urban itinerant traders, craftsmen, professionals, and retail merchants, and, by extension, vehicles of economic and intellectual activity. These pages reveal that it is the Vlachs’ recent history that has played the biggest part in defining their identity.

Subtracts from "The Vlachs: Metropolis and diaspora"

Migratory movements during the 19th century and until 1912

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA VII. The Vlachs in north-western Macedonia 3.3.3. Migratory movements during the 19th century and until 1912 By around the mid-nineteenth century, the network of...

The diaspora and the colonies of the Grammoustian Vlachs

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA VI. The Vlachs of Grammos 2.8.4. The diaspora and the colonies of the Grammoustian Vlachs It is worth mentioning, albeit briefly, the villages and the hut...

Moschopolis, the glory days, 1700–1769

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA V. The Vlachs of Moschopolis and the surrounding area 3.2. Moschopolis, the glory days, 1700–1769 In the eighteenth century, Moschopolis and the local Vlach...

The Arvanitovlachs in Roumeli (Mainland Greece)

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA IV. The Arvanitovlachs 7. The Arvanitovlachs in Roumeli (Mainland Greece) In around 1840, the large Arvanitovlach settlement at Bitsikopoulo was apparently...

The Kupatshari

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA III. The Vlachs of the Northern Pindos: The Vlach villages in the Grevena area 1.3. The Kupatshari Apart from the known Vlach villages, there is another distinct...

The debate about the former extent of Vlahozagoro

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA II. The Vlachs of Zagori and Konitsa 3.2.2. The debate about the former extent of Vlahozagoro According to one out-dated view, the Vlach villages in Zagori were...

The Vlachs of Aspropotamos: The conditions and the agents of development

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA I. The Vlachs of the Southern Pindos The Vlachs of Aspropotamos and Malakassi 7.1 The conditions and the agents of development The difficult circumstances of the...