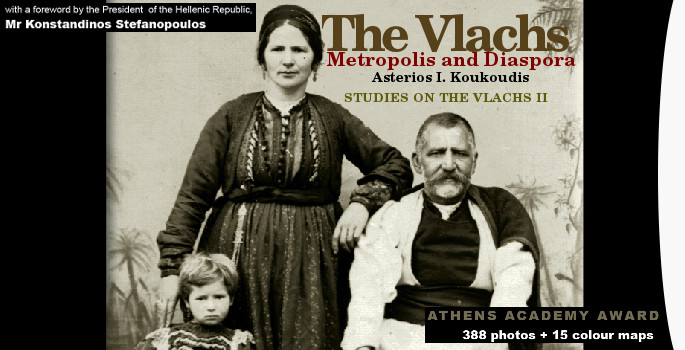

The Vlachs: Metropolis and Diaspora

|

2nd vol. |

After the landmark year 1769, when Moschopolis suffered its first massive collapse, the Vlachs launched their best documented diaspora, from the south northwards. Groups large and small left their ancestral villages along the spine of the Pindos Mountains and moved out into the Balkans and even beyond. Inundating the wider geographical region of Macedonia, they established new settlements in the highlands and colonies in the developing towns. They reached as far as the Rodopi and Balkan Mountains and towns in Bulgaria; they established colonies in towns in Kosovo and Serbia; they crossed the Danube and the Sava to swell the Greek Orthodox communities in the Habsburg Empire and the Danubian Principalities. This account and record of the massive Vlach diaspora clearly shows that Greece itself is the indisputable ‘metropolis’ of the Vlachs.

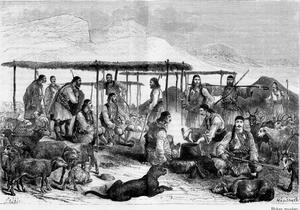

Mr Koukoudis’s research demolishes numerous myths. He shows, for instance, that the Vlachs have not been merely a marginal group of traditional mountain-dwelling pastoral nomads in the modern era. Although their stockbreeding tradition goes back to the Middle Ages, the pastoral nomads are only one part of the Vlach mosaic. From the early 17th century onwards, when they gradually started to make their demographic presence felt in the Balkans, the Vlachs were not only traditional mountain-dwelling pastoral nomads, but also competent fighters (armatoles and klefts), urban itinerant traders, craftsmen, professionals, and retail merchants, and, by extension, vehicles of economic and intellectual activity. These pages reveal that it is the Vlachs’ recent history that has played the biggest part in defining their identity.

The Vlachs: Metropolis and Diaspora

Studies on the Vlachs - 2nd vol.

hard cover 28x21 cm

516 pages, 15 colored maps

388 old black and white pictures

Zitros Publications, Thessaloniki 2003

Foreword by the Director Yannis Z. Drossos

Read it

Read it at Medusa, the digital repository of Veria’s Central Public.

The Vlachs: Metropolis and Diaspora

Studies on the Vlachs - 2nd vol.

hard cover 28x21 cm

516 pages, 15 colored maps

388 old black and white pictures

Zitros Publications, Thessaloniki 2003

Foreword by the Director Yannis Z. Drossos

Photos

Photos

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA

I. The Vlachs of the Southern Pindos - The Vlachs of Aspropotamos and Malakassi

II. The Vlachs of Zagori and Konitsa

III. The Vlachs of the Northern Pindos: The Vlach villages in the Grevena area

IV. THE ARVANITOVLACHS

V. THE VLACHS OF MOSCHOPOLIS AND THE SURROUNDING AREA

VI. THE VLACHS OF GRAMMOS

VII. THE VLACHS IN NORTH-WESTERN MACEDONIA

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA

VII. The Vlachs in north-western Macedonia

3.3.3. Migratory movements during the 19th century and until 1912

By around the mid-nineteenth century, the network of Vlach villages and settlements in this group had more or less assumed its final form, which was affected only by an influx after the 1854 rebellion of transhumant stockbreeders from the Vlach villages near Grevena, who settled mainly in Klissoura, Vlasti, Namata, Eratyra, Siatista, and Tsotyli, and the arrival of Arvanitovlach nomads in various settlements, such as Gorna Belica, Nizepole, Drossopiyi, and Flambouro. This period was marked by escalating economic progress and considerable demographic development. Aravandinos’s figures illustrate the situation nicely. In his monograph on the Vlachs, which was published in 1905 but had been written in 1865 and was based on even earlier data, he reports: 80 Vlach families in Ohrid, 1,050 in Gopes, 650 in Maloviste, 1,250 in Magarevo and Trnovo, 200 in Nizepole, 1,350 in Monastir and the surrounding villages, 450 in Bukovo, 1,500 in Krusevo, 50 in Titov Veles, 700 in Klissoura, 500 in Nymfaio. 400 in Vlasti, and 400 in ‘Kalyvia’,[1] making a total of 8,600 families and about 43,400 Vlachs.[2] His list does not include the Vlach inhabitants of Gorna and Dolna Belica, Struga, Resen, Jankovec, Borino, Trestenik, Prilep, Pissoderi, Namata, and the smaller communities in local towns and kefalohoria, such as Florina, Kastoria, Argos Orestiko, Tsotyli, Eratyra, and Siatista. However, he does mention Vlachs in Bukovo near Monastir, and this may confirm other references[3] to the existence of Vlach communities in villages between Monastir and Pelister, such as Bukovo, Lavci, Brusnik, Dihovo, and Bratin Dol, where the Vlachs lived alongside Slavonic-speaking Christians. Most of them must gradually have gravitated towards Monastir. What is important to note is that most of the Vlach settlements in this group really had quite large populations for the time. They were splendid exceptions in the demography of the area, especially in comparison to the nearby Greek-speaking, Slavonic-speaking, and Albanian-speaking settlements. Another indication of the size and population of some of the Vlach settlements in this group is the fact that, from at least the end of the nineteenth century, Krusevo, Nymfaio, and Klissoura were the seats of three small, but very vigorous nahies.[4]

By around the mid-nineteenth century, the network of Vlach villages and settlements in this group had more or less assumed its final form, which was affected only by an influx after the 1854 rebellion of transhumant stockbreeders from the Vlach villages near Grevena, who settled mainly in Klissoura, Vlasti, Namata, Eratyra, Siatista, and Tsotyli, and the arrival of Arvanitovlach nomads in various settlements, such as Gorna Belica, Nizepole, Drossopiyi, and Flambouro. This period was marked by escalating economic progress and considerable demographic development. Aravandinos’s figures illustrate the situation nicely. In his monograph on the Vlachs, which was published in 1905 but had been written in 1865 and was based on even earlier data, he reports: 80 Vlach families in Ohrid, 1,050 in Gopes, 650 in Maloviste, 1,250 in Magarevo and Trnovo, 200 in Nizepole, 1,350 in Monastir and the surrounding villages, 450 in Bukovo, 1,500 in Krusevo, 50 in Titov Veles, 700 in Klissoura, 500 in Nymfaio. 400 in Vlasti, and 400 in ‘Kalyvia’,[1] making a total of 8,600 families and about 43,400 Vlachs.[2] His list does not include the Vlach inhabitants of Gorna and Dolna Belica, Struga, Resen, Jankovec, Borino, Trestenik, Prilep, Pissoderi, Namata, and the smaller communities in local towns and kefalohoria, such as Florina, Kastoria, Argos Orestiko, Tsotyli, Eratyra, and Siatista. However, he does mention Vlachs in Bukovo near Monastir, and this may confirm other references[3] to the existence of Vlach communities in villages between Monastir and Pelister, such as Bukovo, Lavci, Brusnik, Dihovo, and Bratin Dol, where the Vlachs lived alongside Slavonic-speaking Christians. Most of them must gradually have gravitated towards Monastir. What is important to note is that most of the Vlach settlements in this group really had quite large populations for the time. They were splendid exceptions in the demography of the area, especially in comparison to the nearby Greek-speaking, Slavonic-speaking, and Albanian-speaking settlements. Another indication of the size and population of some of the Vlach settlements in this group is the fact that, from at least the end of the nineteenth century, Krusevo, Nymfaio, and Klissoura were the seats of three small, but very vigorous nahies.[4]

Once the refugees from the Moschopolis and Grammos areas had settled down, it was not long before they re-established their commercial activities and their craft-trades. They brought their flair for commerce and light industry with them to their new settlements and villages and considerably boosted the potential of the older settlements. Thus, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, Pouqueville notes the presence of enterprising Klissourian merchants and transporters making their way along the Balkan highways to Central Europe.[5] For a long time, the various forms of craft-trade, transportation, and retail trade were the basic, and quite lucrative, activities of the inhabitants of almost all the villages and settlements in this group. Their contact with their relations and compatriots in the communities in the northern Balkans and Central Europe, both before and during the mass exoduses in the late eighteenth century, played a decisive role in their further development. Furthermore, there seems also to have been a constant flow of isolated individuals or small family groups migrating to the Habsburg Empire, Serbia, and the Danubian Principalities for a long time after 1769.

The inhabitants of most of the settlements maintained a mixed agricultural and pastoral economy alongside the burgeoning commerce, crafts-trades, and transportation. The scale of the agricultural economy varied from village to village and developed in inverse proportion to commerce. Dolna Belica seems to have been the village most closely involved in farming,[6] though viticulture was not unknown even in Klissoura, which had a largely commercial economy. In most cases, any agricultural production was usually in the hands of labourers and servants hired from the nearby Slavonic-speaking and Greek-speaking villages.[7]

Already in the first half of the nineteenth century, the pastoral economy had begun to contract, as there was an even bigger shift towards craft-trades, commerce, transportation, and periodic emigration. The gap was filled by groups of Arvanitovlach and other Vlach stockbreeders from the northern Pindos, who formed associations with the various villages and eventually, in many cases, settled down in them. Of course, animal husbandry did not die out entirely, nor did it pass exclusively into the hands of the Arvanitovlachs. In Krusevo, old Grammoustian families apparently owned large flocks and herds until the beginning of the twentieth century.[8] In Vlasti and Namata, the inhabitants fell into two distinct and more or less equal groups, the permanently settled inhabitants and the transhumant stockbreeders. The Vlach families who made up the permanently settled group ― the merchants, craftsmen, professionals, migrant workers, and smallholders ― very rapidly lost their Vlach tongue and eventually even denied their Vlach identity and Vlach origins. The process was undoubtedly hastened by the co-existence and intermarriage between Vlach-speakers and Greek-speakers (especially in Vlasti), as also by their very close connections with Greek-speaking centres like Siatista. The transhumant stockbreeders, by contrast, preserved both their use of the Vlach language and a sense of their Vlach identity for much longer. By about 1910, most of the settled residents of Namata had moved for greater safety to nearby Vlasti, leaving the village to evolve into a highland community of transhumant Vlachs, who had themselves, like the people of Vlasti, more or less lost their Vlach tongue.

The departure of most of the settlements in this group from the organised forms of nomadic or transhumant stockbreeding led to a very interesting intracommunal cleavage. In Nymfaio, the settled Vlachs referred to themselves as Armuni (‘Vlachs’ in the Vlach language) and dissociated themselves from both the Vlach-speaking and the non-Vlach-speaking pastoral nomads, to whom they referred collectively as vlahi with a small v and with cultural, professional, and social connotations. This distinction must have arisen out of the long co-existence of Vlach commercial and light industrial communities and communities that were directly connected with the various forms of animal husbandry. The ‘urban’ Vlach communities of merchants and craftsmen in this group disprove the erroneous stereotypical image of the Vlachs which prevails even today.

It is interesting in this respect to note what Konstandinos Nikolaïdis, author of the Etymological Lexicon of the Koutsovlach Language, had to say in 1907. Apart from the nomadic and transhumant Vlachs, he tells us, the Koutsovlachs are primarily a commercial and industrial people, who practise all the professions and all the arts and sciences.[9]

The Skyrian writer and journalist Konstandinos Faltaïs offered an even more illuminating assessment in the inter-war period, when he wrote:

The Latin-speaking Vlachs are a people involved in all kinds of art, craft, and trade. They might be termed the jacks of all trades of the Balkans. More particularly, they engage in silversmithery, weaving, coopery, the manufacture of wooden agricultural implements, saddlery, shoemaking, bronzesmithery, cutlery, religious painting, building, tailoring, charcoal production, carpentry, woodcutting, and cheese-making. They are also muleteers, grocers, inn-keepers, khan-keepers, and more generally merchants, businessmen, and scholars. Most of the rest of the Vlachs in the Balkans are stockbreeders, though not nomads, as is erroneously written. There are very few Vlach farmers, sailors, or manual labourers with no specific trade.[10]

Until the end of the nineteenth century, transportation ― of merchandise, commodities, and people, in numerous caravans ― was almost exclusively handled by the Vlachs in the area under examination. Probably their only rivals in this sphere were the Greek-speakers from such towns as Kozani, Siatista, and Kastoria, and the kefalohoria in Voio. As the basic Ottoman road network developed and the first railway lines were laid, transportation suffered a decline and the inhabitants were obliged to send even more young men away for varying periods of time to find employment and earn their living.[11] At this stage and until the beginning of the twentieth century, the Vlachs were emigrating to, and establishing colonies in, the European territory of the Ottoman Empire and the various Balkan countries. There were some shining exceptions, to be sure, such as the colonies established in Egypt by the Vlachs of this group and the Vlachs from Metsovo.[12] Retail trade reached a turning point in the Balkan towns, and this offered the Vlach inhabitants of the villages and settlements in north-western Macedonia a means of escape from their earlier traditional economy. Their old skills in the spheres of commerce and craft trades were the most valuable qualifications that reinforced their old tendency towards urbanisation.

The inhabitants of Krusevo, both Vlachs and non-Vlachs, were already migrating by the mid-nineteenth century. A lack of productive sources naturally forced them to seek out better opportunities elsewhere, either nearby or far away. From about 1880 onwards, the migrants started taking their families with them, and Krusevite colonies of varying sizes sprang up in almost all the towns in Macedonia. They settled in large numbers in Monastir, Prilep, Kicevo, Ohrid, Skopje,[13] Kumanovo, Kocani, Thessaloniki, Korçë, Ioannina, Gorna Djumaja (Blagoevgrad),[14] Serres, Drama, Nevrokop (Goce Delcev), and as far away as Constantinople. Smaller groups established colonies in Gevgelija, Negotino, Kafadarci, and Kriva Palanka; while others went as far as Athens, Sofia, Vidin, Belgrade, Nis, Bucharest, Alexandria, Cairo, and even Ethiopia, South Africa, the United States, and India.[15] The Krusevites started to leave in greater numbers after the collapse in 1903 of the Ilinden uprising, which was essentially fomented by Bulgaria and centred on Krusevo. As a result of the destruction visited on the inhabitants, especially the Grecoman Vlachs, Krusevite colonies were established and/or strengthened virtually all over Macedonia, as numerous families went to join the men who had emigrated. One typical Krusevite colony was established at this time in nearby Kicevo.[16]

In this period, the people of Gorna and Dolna Belica went in search of better opportunities, mainly in Struga, Debar, Tiranë, and the towns of central Albania.[17] The earlier immigrants from Nizepole and, to a lesser extent, the Arvanitovlachs in the village went to live in Monastir and Thessaloniki. The immigrants from Magarevo and Trnovo established colonies in Monastir, Florina, Thessaloniki, Kocani, Xanthi, Yannitsa, and Aridaia. Some of them went as far as Constantinople, Smyrna, and Egypt, and quite a number went to live in towns in Bulgaria and Romania. The people of Gopes tended to head for towns in Serbia, Bulgaria, and Romania. Smaller groups of them settled in Monastir and Thessaloniki. An even greater number of families from all the Vlach villages in this group moved to Monastir during the armed confrontation over the fate of the Macedonian provinces, especially in the early twentieth century. Sixty families from Maloviste, for instance, are reported to have settled in Monastir at this time.[18] Monastir’s development into a focus of attraction and a vigorous economic centre for large numbers of Vlach immigrants was considerably reinforced by the fact that it was the administrative and economic centre of the vilayet of the same name at that time. The boundaries of the vilayet embraced the most flourishing Vlach settlements in the Balkans.[19]

Migration, together with the confrontations between the Balkan states over Macedonia, pushed the Vlach colonies in Ohrid and Titov Veles into a decline. In the nineteenth century, the Vlachs of Ohrid made a name for themselves in the fur trade and in transportation. Their activities took them as far as the great commercial centres of Europe, such as Leipzig and the Danubian Principalities, and as far as Constantinople. Until the establishment of the Bulgarian Exarchate, the Vlachs of Ohrid were running a Greek school in each of the town’s two Vlach districts, and quite a number of the young people, both Vlach-speaking and Slavonic-speaking, went to study in Athens and Ioannina. However, the Vlach colony in Ohrid was not destined to take root and flourish. By the mid-nineteenth century, its members were already migrating in large numbers, seeking commercial opportunities and a better life elsewhere.[20] In fact, towards the end of the nineteenth century, when the Bulgarian movement in the town was gaining ground, many of the Vlach families apparently went over to the Exarchate, possibly in an effort to blend in with their environment. However, the most vigorous of the Vlach families, and a few Slav families too, who remained pro-Greek and loyal to the Patriarchate, were forced to leave Ohrid. Most of them went to Monastir and, after 1912, to Thessaloniki.[21]

The ‘Greek Vlach’ community (as it is termed in Greek diplomatic documents of the nineteenth century) in Titov Veles declined in the same way. In 1894, after the Bulgarian ecclesiastical movement had taken hold in the town and the surrounding area, the Vlachs of Titov Veles remained loyal to the Patriarchate of Constantinople, and the small Greek Orthodox Patriarchist community (which was made up solely of the local Vlachs, and numbered up to about 200 families) continued to function. The community dwindled when the Romanian movement, assisted by the Bulgarians, made its appearance.[22] From 1912 onwards, the leaders and the wealthier members of the community left for Greece and almost all of them settled in Thessaloniki. A few other families went to Romania or were assimilated by the inhabitants of Serbia and Fyrom.[23]

The people of Pissoderi, who were traditionally khan-keepers and inn-keepers on the Balkan communications routes, established small colonies at Resen, Monastir, Florina, Argos Orestiko, and Kastoria. Most of them, mainly the most enterprising ones, left to live elsewhere. Between 1830 and 1912, eighty families from Pissoderi reportedly settled in parts of what was then southern Serbia, while others migrated to towns in Russia, Romania, and Bulgaria, and yet others went to join the colonies in Egypt.[24]

In the same period, most of the men of Nymfaio were supporting their families by working as goldsmiths, tailors, dyers, and transporters. To begin with, they were itinerant craftsmen and artisans, and they gradually established colonies in a number of towns and kefalohoria in Macedonia and beyond, as far as Përmet in southern Albania and Thiva (Thebes) in southern Greece. Many of them, starting off mainly as goldsmiths, developed into enterprising merchants ― dealing mainly in tobacco ― not only in the Balkans but also in Constantinople, Romania, Egypt, and even Sweden. The men working away from home were gradually joined by their families, particularly in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, forming some noteworthy Nevestian colonies, some small, others quite large, in Florina, Kastoria, Monastir, Edessa, Naoussa, Veria, and Yannitsa, with the largest and most vigorous community being in Thessaloniki. In Eastern Macedonia, they met up with earlier refugees from Nymfaio. With the influx of new migrants from Nymfaio, small but vigorous and well-to-do colonies of, mainly, goldsmiths and tobacco mechants sprang up in Serres, Drama, Prossotsani, Doxato, Kavala, and Xanthi. It must have been through Kavala and Constantinople that the Nevestians forged their connections with Egypt, where they established vigorous, wealthy colonies.[25]

The people of Klissoura already had close connections with the colonies in the Habsburg Empire and Serbia, and that was where they chose to go until the beginning of the twentieth century, establishing rich colonies in Vienna, Budapest, Dresden, Zemun, Belgrade, Pancevo, Nis, Bucharest, Jassy, and Odessa. More than 2,000 families reportedly made their way to these Klissourian colonies, a probably exaggerated figure, but certainly indicative of the magnitude of the migrations from Klissoura. Unlike the inhabitants of the other Vlach villages and settlements in this group, the Klissourians did not disperse as merchants and craftsmen to the towns and kafalohoria of Macedonia (apart from the internal migrants who went to nearby Kastoria, Amyndaio, and Ptolemaïda). During the nineteenth century, Klissoura evolved into a vigorous commercial and light industrial centre and a transit centre that rivalled Kastoria. In its heyday it may have had as many as a thousand houses, with more than a hundred shops and light industrial establishments in its commercial centre. Numerous Vlach caravans, even from other places, such as Veria and Katerini, set out from Klissoura for all the major commercial centres in the Balkans, carrying all kinds of marketable goods. Emigration halved the population between 1870 (6,400 inhabitants) and 1912 (3,000 inhabitants). Most of the Klissourians remained within the Ottoman Empire at this time. From 1890 onwards, they headed in large numbers for Constantinople and Thessaloniki. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the colony in Constantinople comprised about eighty enterprising merchants and craftsmen and a total of 300 souls. A vigorous association named Profitis Ilias was established to help organise the colony better. It was disbanded after 1908, and the most dynamic members moved mainly to Thessaloniki, where the old Klissourian colony played a leading role in the affairs of the Greek Orthodox community. In 1907, the Klissourians set up the Ayios Markos Association. A smaller group, mainly of tobacco merchants, settled in Kavala at this time.[26]

Throughout the nineteenth century, the Blatsiots (from Vlasti), whether descended from the Vlach refugees of 1769 onwards or from Greek-speakers living in Vlasti, continued to maintain their contact with, and to emigrate to, the colonies in the Habsburg Empire, the Danubian Principalities, and Serbia, accompanying the Vlach or Grek caravans heading north across the Danube. The colonies which they established in the towns in Eastern Macedonia in the first half of the nineteenth century grew considerably between the 1860s and the beginning of the twentieth century. During this latter period, those who left Vlasti were migrants, not fugitives, and were members of the merchant and light industrial class, not transhumant stockbreeders. Thus, most of the Blatsiots who went to Thessaloniki, Serres, Kavala, Drama, Constantinople, Egypt, and Romania at this time had almost forgotten the Vlach language.[27]

Apart from the colonies that were established by the more enterprising members in various distant places, other Vlach craftsmen and retailers dispersed to various villages, most notably to the kafalohoria of Western Macedonia. The first small Vlach community in Florina was established at the end of the nineteenth century by merchants and craftsmen from the surrounding villages, most notably Pissoderi.[28] Vlach merchants and craftsmen from Klissoura and Vlasti seem to have been the first Christians to settle in a professional capacity in the then Turkish town of Ptolemaïda (Kaïlaria). In the same period, Vlach merchants and craftsmen established their families in Amyndaio (Sorovitsevo), and stockbreeders from Vlasti settled in Mylohori (Linga) in Eordaia province. D. M. Brancoff offers some interesting statistics, recording the presence of small groups of Vlach families among the inhabitants of villages near Kastoria, such as Vassiliada (Zagoritsani), Pendavryssos (Zelegosdi), Korissos (Gorendzi), and Kalohori (Dobrolitsa), as also in Vatohori (Bresnitsa) near Florina.[29]

Perhaps the most accurate evidence relating to the social and economic identity and the migratory practices of the members of the Vlach communities and settlements in north-western Macedonia is found in the List of the Males of the Greek Orthodox Community of Resen in the Year 1912. Resen, 10 February 1912. It offers valuable information about the 220 Vlach men who constituted the small, but vigorous Greek Orthodox community of Resen. According to the list, 34.5 per cent of the members of the community were migrants. Of these, half had emigrated within the bounds of the geographical region of Macedonia or to Constantinople, while the other half had gone to Balkan countries or even to America. Each one’s occupation is listed, and so we know that 64 per cent of them, whether migrants or not, were merchants, craftsmen, and professionals.[30]

Of all the known published statistics relating to the Vlachs in north-western Macedonia in the early years of the twentieth century (1900–1912), those gathered by the Oecumenical Patriarchate in 1905, despite errors and omissions, are perhaps the most informative. The figures are as follows: Monastir 2,107 Vlach families, Magarevo 454, Trnovo 481, Nizepole 186, Krusevo 1,174, Prilep 75, Maloviste 304, Gopes 324, Resen 56, Jankovec 28, Istok 130, Ohrid 121, Struga 17, Gorna Belica 208, Dolna Belica 176, Pissoderi 140, Florina 29, Drossopiyi 230 (?), Flambouro 150 (?), Nymfaio 400, Kalyvia Morihovou 60, Klissoura 515, Krystallopiyi 30, and Argos Orestiko 120; making a total of 7,515 Vlach families.[31] But if we also take into account the Vlach families who were certainly living in Trestenik and Borino near Krusevo, in Kastoria, Grammousta, Vlasti, Sissani, Namata, Tsotyli, Eratyra, Siatista,[32] and Kozani,[33] not to mention some nomadic Arvanitovlach falkaria in the area (in Ilino and Leva Reka near Resen and elsewhere), then the total number of Vlachs in the north-west Macedonian group must certainly have been in excess of 40,000. This must be a fairly accurate figure, because, for the same Vlach villages and settlements in this area, Weigand (1894) gives 46,430 Vlachs, Kancev (1900) 36,398, and Brancoff (1905) 37,004. It is thus clear that Margaritis-Rubin’s figure of 88,750 in 1894–1913 is exaggerated.[34] It should also be noted that at the beginning of the twentieth century, of all these Vlach villages and settlements, only Klissoura, Nymfaio, Pissoderi, Maloviste, Gopes, Kalyvia Istok, and the less organised Arvanitovlach hut settlements in the mountains were inhabited exclusively, or almost exclusively, by Vlachs.

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA

VI. The Vlachs of Grammos

2.8.4. The diaspora and the colonies of the Grammoustian Vlachs

It is worth mentioning, albeit briefly, the villages and the hut settlements which the Grammoustians colonised or established ― though they cannot be precisely dated, because the exoduses succeeded one another in waves. Grammoustian falkaria appeared in Krusevo and the surrounding area, seeking summer pastures, before the people of Nikolicë settled there. At first, when Krusevo was evolving into a village with a settled Vlach population, the Grammoustians lived there only in summer. Later on, during the nineteenth century, most of them abandoned transhumance and settled in Krusevo for good. A little to the south of Krusevo, a small settlement with an exclusively Vlach population was established and named Borino. Borino reportedly had about 100 families and a brief life-span, for an attack by Arnaut raiders sent the inhabitants fleeing to Krusevo, where they established a new district and named it Birina. Apparently, quite a number of the Grammoustians of Borino were not only stockbreeders but also excellent metalworkers. Two rather small, exclusively Grammoustian settlements were established at Carnus (or Mukos) and Kadijica near the Babouna pass between Prilep and Titov Veles. Carnus reputedly had the probably inflated number of 300–400 families of stockbreeders and caravan drivers and did not thrive. In around 1850, again after a predatory raid by Arnauts, this time from Shkodër, the Grammoustians of Carnus dispersed, and many of them went to Krusevo, Stip, and Tetovo. Those who settled in Tetovo apparently included some excellent gunsmiths.[1] Following the destruction of Carnus and Kadijica, some of the inhabitants probably went and joined the nomadic falkaria and the Grammoustian hut settlements in the more easterly parts of Macedonia. References to Grammoustian metalworkers and gunsmiths lend support to the view that Grammousta was not just a village of transhumant Vlach stockbreeders, but also had inhabitants who were engaged in commerce and craft trades. As we have seen, smaller groups of Grammoustians, mainly stockbreeders, helped to colonise Magarevo, and also Trnovo and Nizepole on Pelister, together with Vlach fugitives from other areas.

It is worth mentioning, albeit briefly, the villages and the hut settlements which the Grammoustians colonised or established ― though they cannot be precisely dated, because the exoduses succeeded one another in waves. Grammoustian falkaria appeared in Krusevo and the surrounding area, seeking summer pastures, before the people of Nikolicë settled there. At first, when Krusevo was evolving into a village with a settled Vlach population, the Grammoustians lived there only in summer. Later on, during the nineteenth century, most of them abandoned transhumance and settled in Krusevo for good. A little to the south of Krusevo, a small settlement with an exclusively Vlach population was established and named Borino. Borino reportedly had about 100 families and a brief life-span, for an attack by Arnaut raiders sent the inhabitants fleeing to Krusevo, where they established a new district and named it Birina. Apparently, quite a number of the Grammoustians of Borino were not only stockbreeders but also excellent metalworkers. Two rather small, exclusively Grammoustian settlements were established at Carnus (or Mukos) and Kadijica near the Babouna pass between Prilep and Titov Veles. Carnus reputedly had the probably inflated number of 300–400 families of stockbreeders and caravan drivers and did not thrive. In around 1850, again after a predatory raid by Arnauts, this time from Shkodër, the Grammoustians of Carnus dispersed, and many of them went to Krusevo, Stip, and Tetovo. Those who settled in Tetovo apparently included some excellent gunsmiths.[1] Following the destruction of Carnus and Kadijica, some of the inhabitants probably went and joined the nomadic falkaria and the Grammoustian hut settlements in the more easterly parts of Macedonia. References to Grammoustian metalworkers and gunsmiths lend support to the view that Grammousta was not just a village of transhumant Vlach stockbreeders, but also had inhabitants who were engaged in commerce and craft trades. As we have seen, smaller groups of Grammoustians, mainly stockbreeders, helped to colonise Magarevo, and also Trnovo and Nizepole on Pelister, together with Vlach fugitives from other areas.

It is difficult to be very specific about the Grammoustians’ highland summer hut settlements, owing to their very nature. They frequently broke up, and their population fluctuated, or else they were inhabited only for a few years. Some of these settlements evolved into permanent summer villages and organised highland communities. Most of them, however, until they were finally abandoned, remained simple summer hut settlements with a small population, and they very often do not appear in the various official and unofficial statistics. Nevertheless, I shall try to present them as fully as possible, at least as they had taken shape by around 1900.

The hut settlement near Ano Koryfi (Rodovo) was established in the Morihovo area on the south-eastern flank of Vorras, but it survived only until the end of the first decade of the twentieth century, when most of the families moved to Edessa. The settlements of Megala Livadia and Mikra Livadia were established on Païko, among the settled Moglena Vlachs, and began to take on the form of permanent semi-nomadic highland communities when the Grammoustians and a few refugees from Moschopolis settled there and were later joined by refugees from Perivoli and Samarina. We shall investigate the Rodovo and Livadia settlements in more detail later on.

A quite remarkable group of Grammoustian hut settlements sprang up in the more easterly parts of Macedonia, on the slopes of Orvilos or Pirin, and more specifically at Lopovo, Bazdovo, Satrovo, and Popovi Livadi in what is now Bulgaria, and Laïlias in Greece. There were also some smaller settlements, which will be discussed in another study. Another group of settlements was established in the Rodopi, where, after the borders were drawn in 1878, some remained in Ottoman territory and others found themselves in Eastern Rumelia. Pizdica, Kartal al Yanku, Cakmak, Krva Reka, Zalti Kamen, the hut settlement near Kostandovo, and the largest of the settlements, Bakica or Kurtovo, were in Eastern Rumelia. The Grammoustians in this group came to be known as ‘Kutruviani’, after the name of their largest settlement. According to Weigand, shortly before 1907 these settlements had about 305 huts altogether and a population possibly in excess of 2,000. On Ottoman territory, Grammoustian hut settlements were established at Karamandra and Sufandere, and also alongside the settlements of Belica, Goldovo, Dobarsko, Draglica, Jakoruda, and Bacevo, and near the market town of Razlog. This group of Grammoustians came to be known as ‘Razlukiani’. According to statistics collected by the Greek consular authorities in around 1906, it was about 2,000 strong.[2]

Another group came into being on Mount Rila, both on Ottoman and on Bulgarian territory. Some of the Grammoustians on Bulgarian territory had apparently passed through the Orvilos area first. The settlements there became permanent after Bulgarian autonomy was recognised in 1878. Ravna Buka, Besbunar, and Kostenec Banja were on Bulgarian territory; the summer hut settlements at Dobropole, Risovo or Hrisovo, Argacic, Bistrica, and Bakir Tepe, and the winter settlements at Blagoevgrad (Gorna Dzumaja), Strumski Ciftlik, Gramada, and Krupnik were on Ottoman territory. A few smaller falkaria also set up summer hut settlements on the western slopes of the Balkan Mountains, such as Ladzene near Anton in the area of Pirdop.[3] According to Weigand, the group on Rila was 1,500–2,000 strong. The Grammoustians who had their summer settlements in the mountains in Ottoman territory every winter inundated the plains along the Strymon, the Drama plain, and the low coastal areas between Ierissos and Porto Lagos in search of grazing grounds; while those in Bulgaria and Eastern Rumelia sought their winter pastures towards the Danube and along the Maritsa/Evros valley as far as Adrianople and the grasslands of Eastern Thrace.

Two hut settlements, Cernodol and Malesevo, were established on Ograzden and Kadijica in what is now Fyrom. There were a considerable number of summer hut settlements in the highland pastures on Osogovo, also in Fyrom, at Kalin Kamen, Kitka, Ponikva, Lopen, Jamiste, Kostarica (or Semeri), Ozdenica, Lisec, Stanci, and Duraska, and slightly further north, on German, were Bara, Vakuf, and Osice. There were at least two summer settlements on Mount Golak near Trsino. On Mount Plackovica, there were summer hut settlements at Catal Cesme, Lisec, Kartal, Cepino, Adjinica, Kukla, Kolarnica, Karatepe, Asanlija, Cokonica, Leonica, Blatec, and Teranci. According to Weigand, at the beginning of the twentieth century all these highland hut settlements together had 500 huts and possibly more than 3,000 inhabitants. According to a Greek consular document of the same period, there were 314 huts in all and possibly around 2,000 inhabitants.[4] In winter, they went down to the Kumanovo plain and along the Vardar/Axios valley to Kilkis, the lake basin of Lagadas, Kalamaria, and as far as Halkidiki. During the twentieth century, the population of these highland hut settlements gradually abandoned pastoral nomadism and eventually settled mainly in lowland villages and towns in the eastern provinces of Fyrom, most notably in the provinces of Kocani, Stip, Ovce Pole, and Titov Veles, along the valleys of the Vardar and its tributary Bregalnica.

To these settlements we must also add those which were established within the then borders of Serbia, between Pirot and Vranja, on the Stara Planina, Gaveska Planina, Sljep, Vidlic, and Suha Planina Mountains and as far as the slopes of Kapaonik on the Serbia–Kosovo border.[5] Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the falkaria on Kapaonik reportedly had 80,000 sheep and 2,000 pack-animals;[6] but they seem to have disappeared without trace.

Some of these settlements were large, with more than a hundred families, while others had no more than fifteen or twenty families. However, their great number and the extent of their dispersal alone gives us some idea of the astonishing magnitude of the population drain from Grammousta and the surrounding Vlach settlements on the slopes of Grammos. All this confirms the fact, that, until the late eighteenth century, Grammousta was indeed one of the largest Vlach communities. So it would be no exaggeration to say that, until the end of the eighteenth century, and even more so in the glory days before this, there were at least 3,000 families and possibly more than 15,000 souls living in Grammousta and its satellite settlements.

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA

V. The Vlachs of Moschopolis and the surrounding area

3.2. Moschopolis, the glory days, 1700–1769

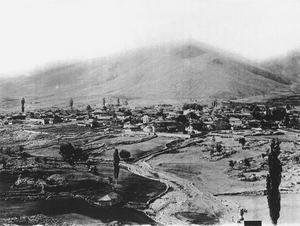

In the eighteenth century, Moschopolis and the local Vlach settlements attained the peak of their development and prosperity; but this was accompanied by a number of insuperable problems, which eventually led to disaster and decay. The foundations of this glorious period had been laid in the seventeenth century, when Moschopolis was growing, not only demographically, but also economically and culturally. One indication of this development was the construction of the Monastery of St John the Baptist in around 1630. Some studies describe Moschopolis as the second largest town in the Ottoman Balkans after Constantinople, though this is in fact unlikely if we consider such cities as Thessaloniki and Adrianople. Nonetheless, it must have been the only town of its size with an exclusively Christian population. It had six large, organised districts and possibly more than seventy churches, though this is probably an exaggerated figure. Although the various sources frequently disagree about the precise number of houses and residents, in around 1760 the town reportedly had somewhere between 20,000 and 70,000 inhabitants and perhaps as many as 12,000 households. These figures seem unlikely for the period, especially in view of the picture we have of Moschopolis from 1769 onwards. The town covered a vast area and occupied much of the now bare plateau and the low slopes round about. It may not be so rash, after all, to accept that the population reached 40,000 in its most prosperous period.[1]

In the eighteenth century, Moschopolis and the local Vlach settlements attained the peak of their development and prosperity; but this was accompanied by a number of insuperable problems, which eventually led to disaster and decay. The foundations of this glorious period had been laid in the seventeenth century, when Moschopolis was growing, not only demographically, but also economically and culturally. One indication of this development was the construction of the Monastery of St John the Baptist in around 1630. Some studies describe Moschopolis as the second largest town in the Ottoman Balkans after Constantinople, though this is in fact unlikely if we consider such cities as Thessaloniki and Adrianople. Nonetheless, it must have been the only town of its size with an exclusively Christian population. It had six large, organised districts and possibly more than seventy churches, though this is probably an exaggerated figure. Although the various sources frequently disagree about the precise number of houses and residents, in around 1760 the town reportedly had somewhere between 20,000 and 70,000 inhabitants and perhaps as many as 12,000 households. These figures seem unlikely for the period, especially in view of the picture we have of Moschopolis from 1769 onwards. The town covered a vast area and occupied much of the now bare plateau and the low slopes round about. It may not be so rash, after all, to accept that the population reached 40,000 in its most prosperous period.[1]

Not only Moschopolis, but the surrounding Vlach villages also amassed a large number of inhabitants for that time. Although the figures offered by the various studies seem exaggerated, Niçë, Llëngë, Grabovë, Shipckë, and the Albanian-speaking Vithkuq must have been large and vigorous market towns following close on the heels of the progressive Moschopolis.[2] Their natural locations protected them from the pressures of Arnaut feudal lords both great and small, and they became vigorous local markets for the surrounding population, maintaining independent relations with the commercial centres of the Balkans and Europe.[3] Each of these local settlements may eventually have had a population of between 5,000 and 10,000.

Socially, Moschopolis was divided into three basic classes. At the top were the notables, the oldest, powerful families. The wealthy and frequently immigrant merchants and craftsmen made up the very vigorous middle class. And at the bottom of the pyramid were the simple labourers, artisans, muleteers, woodcutters, shepherds, and farmers. As far as possible, the administration of the town was in the hands of the inhabitants themselves, mainly the members of the upper and middle classes. Each district appointed an elder, and so at first the community council had six members, one of whom acted as chairman. The chairman was elected by vote and the result ratified by a firman. Later on, there were twelve councillors, when a kocabasi was included from each district, charged with collecting the taxes. But apart from the community council, an active role in the town’s public affairs was also played by the powerful guilds, organised professional bodies which seem to have numbered between thirteen and seventeen, though there are reports of even more. The town’s security was guarded by a small garrison of Arnauts, who were required to defend the surrounding mountain passes leading to and from Moschopolis and ensure free passage for transport and trade.[4]

Moschopolis drew its wealth and strength from commerce and the various craft trades. As in the case of other well-developed Vlach communities (such as Metsovo, Syrrako, and Kalarites), progress and development were primarily based on stockbreeding. But in fact Moschopolis was well in advance of the others by the seventeenth century, and it was probably Moschopolis which blazed the trail for the other Vlach and non-Vlach highland communities. Thanks to abundant raw materials and labour, the wool industry boomed. The early cottage industry in woollen goods evolved into organised light industrial production and eventually into trade in both the final products and the raw materials. By trading in their own products and amassing capital, the townsfolk gradually developed wider ranging commercial, compradorial, and light industrial activities, and the caste of the so-called pragmateftades was born (pramatefts or pramateftadz in Vlach, ‘itinerant trader’). The craftsmen organised and strengthened the institution of the guilds. There were guilds of grocers, tailors, goldsmiths, butchers, coppersmiths and ironsmiths, gunsmiths, cordwainers, and many more, and they played an important part not only in economic development and local politics, but also in cultural progress, for they reportedly paid for scholarships to cover indigent children’s education in schools both in Moschopolis and in Europe.[5]

However, the greatest economic and cultural wealth came with the development of connections with Europe and the shift towards compradorial activities. It is not unlikely that there were Moschopolitans among the merchants in the Greek Orthodox community in Venice as early as 1537. In that year, the immigrants in Venice built a Greek Orthodox church and a Greek school.[6] In the course of the seventeenth century, the Moschopolitans, via Durrës, forged close commercial relations both with Venice and Ancona and with other Italian ports on the Adriatic.[7] Enterprising merchants transported goods there from all over the central Balkans and as far away as the Danubian Principalities. And they returned not only with other merchandise or capital, but also with valuable knowledge. The merchants were followed on their voyages to Venice by young Moschopolitans wishing to study there or to serve apprenticeships with important merchants. It is interesting to note that, in 1694–1703 and 1712–16, a scholarly priest from Moschopolis named Ioannis Halkias served as director of the Flanginis Institute and preacher in the Greek Orthodox Church of St George in Venice, having previously served as parish priest to the Greek Orthodox community in Leghorn.[8] In this period, the Moschopolitans were travelling as far afield as Constantinople, not only on their own or on community business, but performing services for the Venetians.[9]

Relations with Venice continued until about 1761. During this time, quite a number of Moschopolitans registered on the municipal roll of the Greek Orthodox community of Venice and do not seem to have differed in any way from the other members. But as Venetian trade began to decline, the Moschopolitans, like other Vlach and non-Vlach merchants from various towns in Macedonia, set their sights on Central Europe, and started accompanying the numerous caravans heading north.[10] The Treaties of Passarowitz (1718) and Belgrade (1739) between the Ottoman and Habsburg Empires proved especially favourable to this new trend. Thus, from 1718 to 1774 Moschopolitans settled en masse in the Habsburg dominions. Some went as far as Warsaw in Poland and Leipzig in Germany. At first they were only men, and mainly young men, seeking opportunities for trade and/or permanent residence. Their wide and varied commercial and light industrial activities soon led them to establish colonies both in Central Europe (including Vienna, Budapest, Szentendre, Miskolc, Kecskemét, Timisoara, Novi Sad, and Zemun) and in various commercial and administrative centres in Macedonia, Thessaly, Epiros, and Albania. Enterprising Moschopolitan merchants and craftsmen also travelled to and worked at the major annual fairs in these Ottoman provinces. The travellers’ journeys, trading activities, and remittances soon nurtured even greater growth and progress.[11]

Economic prosperity paved the way for cultural development, as is evidenced by the fact that nine splendid new churches were built between 1715 and 1760. Those which are still standing are incontrovertible witnesses to the high noon of Moschopolis.[12] Even before 1700 there was an organised Greek school. The school developed along with, and met the demands of, the vigorous, progressive society that built it. The teachers were highly educated and influential, and the Moschopolitans also took care to engage outstanding scholars from elsewhere to teach there. In 1744, new subjects were added to the curriculum and the Moschopolis school became the celebrated New Academy; and in 1750, when it moved to new premises more appropriate to its fame and requirements, it was renamed the Hellenic Phrontistery. The course of study it offered was possibly one of the most advanced which a Christian could attend in the Balkans at that time, essentially making Moschopolis one of the most important centres of the Greek Enlightenment. The library was one of the largest and most splendid in the Balkan provinces in those days. Under the aegis of the New Academy, residential premises were provided to accommodate and feed students who came to attend the Moschopolis schools from all over the Balkans. Among the social institutions that came into being was the Poor Fund, a community fund whose purpose was to provide relief for the less privileged townsfolk. One of the most admirable establishments in this singular town was the printing-house, which began operating in 1720 or in 1735. It used Greek type, and was therefore the second Greek printing-house in the Ottoman Empire after that of Constantinople (1627). Many of the young Moschopolitans and the students who came from elsewhere to attend the town’s schools went on to continue their education in schools and institutions in Austria, Germany, Italy, and even Holland.[13] So Moschopolis was justly dubbed the ‘New Athens’. Apart from in Moschopolis, a strong educational tradition also developed in Vithkuq, Shipckë, and Korçë, where Greek schools were operating in the eighteenth century.[14]

It is worth noting that the influx into the market and the schools of Vlach-speaking Moschopolis of immigrants, traders, teachers, and students from all over the Balkans, who spoke Vlach, Greek, Albanian, and Bulgarian, led to the publication of two lexicons that were really quite splendid for their time. In those days, when the various nationalist movements were unknown, at least in the form in which they developed in the Balkans after the mid-nineteenth century, the enterprising, progressive Moschopolitans saw no harm, but rather practical benefit, in recording and studying the Vlach, Albanian, and Bulgarian tongues. The compiling and publication of the lexicons was intended more as an aid to the education of the various non-Greek-speaking Christians, because the education that was offered in Moschopolis (and elsewhere too) was essentially regarded as Greek. Theodoros Anastassios Kavalliotis, one of the most brilliant Moschopolitan teachers and a leading light in the Greek scholarly world, published his Protopiria (Starting out) in Vienna in 1770. It includes a 1,170-word lexicon of the simple modern Greek, Vlach, and Albanian languages.[15] Kavalliotis’s efforts were continued by one of the New Academy’s most important teachers, the priest and monk Daniil Moschopolitis, with his Introductory Teaching containing a Four-Language Lexicon of the four common dialects, namely simple Romaic [modern Greek], Moesian Vlach, Bulgarian, and Albanian, which was published or written in Moschopolis in 1764 and republished in Vienna in 1794 and 1802.[16]

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA

IV. The Arvanitovlachs

7. The Arvanitovlachs in Roumeli (Mainland Greece)

In around 1840, the large Arvanitovlach settlement at Bitsikopoulo was apparently destroyed and abandoned following raids by Arnaut brigands. Most of the families who had been living there since Ali Pasha’s time fled to the safety of the newly established Greek state, where they continued their nomadic pastoral lifestyle, moving between the Agrafa Mountains and other highland areas in Evrytania, and in Epiros too, in Ottoman territory, and the lowland areas of Xiromero in Akarnania as far as the mouth of the Aheloös. Heuzey reports that in 1856 they numbered 800 families (4,000 to 5,000 souls) and established twelve large winter settlements with between fifty and a hundred families each.[1]Between 1865 and 1870, they gradually started to establish more permanent dwellings in these winter abodes. The villages which they established at this time are now the southernmost Vlach settlements: Stratos (Sourovigli or Yannika), Ohthia (Ohtou or Payeïka), Agrambela (Dayanda), Gouriotissa (Katsarou), Paliomanina (Koutsobina), Strongylovouni (Stournari or Gakeïka), and Manina Vlizianon (Kaledzi).[2] It should be noted that the Arvanitovlachs of Roumeli have come to be generally known as Karagounides. According to an article in the periodical Pandora, in about 1856 the Arvanitovlachs of Aitolia and Akarnania numbered about 2,000 and had 100,000 sheep, which gave the Greek state what was then a considerable income of 20,000 drachmas in taxes.[3] Weigand reports that in 1888–9 there were 2,625 souls in the seven former winter settlements of the Arvanitovlachs of Akarnania, which gradually evolved into permanent agricultural and pastoral villages; and he gives much more information about their traditional organisation.[4]

In around 1840, the large Arvanitovlach settlement at Bitsikopoulo was apparently destroyed and abandoned following raids by Arnaut brigands. Most of the families who had been living there since Ali Pasha’s time fled to the safety of the newly established Greek state, where they continued their nomadic pastoral lifestyle, moving between the Agrafa Mountains and other highland areas in Evrytania, and in Epiros too, in Ottoman territory, and the lowland areas of Xiromero in Akarnania as far as the mouth of the Aheloös. Heuzey reports that in 1856 they numbered 800 families (4,000 to 5,000 souls) and established twelve large winter settlements with between fifty and a hundred families each.[1]Between 1865 and 1870, they gradually started to establish more permanent dwellings in these winter abodes. The villages which they established at this time are now the southernmost Vlach settlements: Stratos (Sourovigli or Yannika), Ohthia (Ohtou or Payeïka), Agrambela (Dayanda), Gouriotissa (Katsarou), Paliomanina (Koutsobina), Strongylovouni (Stournari or Gakeïka), and Manina Vlizianon (Kaledzi).[2] It should be noted that the Arvanitovlachs of Roumeli have come to be generally known as Karagounides. According to an article in the periodical Pandora, in about 1856 the Arvanitovlachs of Aitolia and Akarnania numbered about 2,000 and had 100,000 sheep, which gave the Greek state what was then a considerable income of 20,000 drachmas in taxes.[3] Weigand reports that in 1888–9 there were 2,625 souls in the seven former winter settlements of the Arvanitovlachs of Akarnania, which gradually evolved into permanent agricultural and pastoral villages; and he gives much more information about their traditional organisation.[4]

Aravandinos reports that, already in Ali Pasha’s time, some Arvanitovlach groups were settled and cut off in the highlands of Akarnania and Evrytania.[5] It is difficult to know exactly what he means by this laconic observation; unless he is referring to the Vlachs whom Pouqueville found living in a group of villages on the southern slopes of Panaitoliko, on the border between Aitolia and Evrytania, and whom he calls Kossiniot Vlachs or Bomieis. According to Pouqueville’s records, the most important village in this group was Kossina, now Kokkinovryssi, and the Kossiniot Vlachs numbered 1,200 families in all. In 1807, the Vlachs of Kossina and the surrounding villages found themselves at odds with Ali Pasha and were forced out of their homes. After this they headed for Mount Aninos or Iti, and became fully nomadic stockbreeders, dispersing all over eastern Roumeli, from Othri to Parnassos, Elikonas, and Parnitha in Attica.[6] Regarding the population in Attica, Pouqueville distinguishes the settled Arvanites from the Vlachs, pointing out that the Vlachs of Attica were pastoral nomads and their presence there was seasonal. In the winters, some falkaria from the Vlach villages in the Pindos, and also on Parnassos, dispersed beyond the traditional Thessalian winter pastures as far as the lowlands of Viotia and Attica, where they grazed their flocks and sold the woollen goods which they produced in their highland communities.[7]

In 1834, immediately after the birth of the new Greek state, another European traveller, Gustave d’Eichtal, reports the existence of nomadic pastoral Karagounides (Arvanitovlachs) in eastern Roumeli. A falkari was setting up its winter quarters in the area of Atalandi at that time, in connection with which d’Eichtal says something very interesting: he hopes that these Arvanitovlachs will not leave the territory of the fledgling Greek kingdom, but rather use their wealth and labour to help build up the small, poor, newly-independent Greece. He observes that, although they have no inclination towards farming, they could turn their drive and vigour to craft-trades and commerce.[8] In 1852–4, the French traveller Edmond About met pastoral Vlach nomads on the outskirts of Athens and gives quite a vivid account of how these people, who were probably Arvanitovlachs, provided the Athenians with their Easter lambs. He leaves no room for doubt, for he observes that the Vlachs who were living in Attica at this time spoke a corrupt Latinate language.[9] In the same period, François Lenormant also mentions the existence of these, probably Arvanitovlach, nomads in the same areas, and notes that some of them overwintered at Dafni Monastery, just outside Athens.[10]

After the birth of the Greek state, the only major settlement occupied by any considerable number of the Arvanitovlach families who were scattered about eastern Roumeli was Imirbei or Birbili, now Anthili, just outside Lamia. In 1833, the hitherto Turkish-owned çiftlik of Anthili was bought by the Dzallases, a wealthy ethnic Greek family from Vienna with roots in Korçë. Intending to make their newly acquired estate productive, the Dzallases invited share-croppers to settle and work in the then uninhabited çiftlik of Anthili. Shortly after 1850, a group of some fifty Arvanitovlach families settled alongside the few Greek-speaking and motley share-croppers. They had previously tried to establish a new permanent settlement at Vardari near Mendenitsa. According to local traditions, one reason why they settled en masse in Anthili was the fact that the Dzallases were also Vlach-speakers. The Arvanitovlachs of Anthili gradually became farmers and stockbreeders, though for several decades they retained a summer settlement at Liathitsa near Damasta Monastery on the slopes of Kallidromo. Smaller groups of Arvanitovlach families, offshoots of the Anthili families, settled in Mendenitsa, Molos, and Exarhos.[11]

We cannot be absolutely certain whether the Arvanitovlachs of Anthili and eastern Roumeli in general were all descended from the Vlachs of Kossina or whether their ancestry lay with Arvanitovlachs who, like those of Aitolia and Akarnania, entered Greek territory then or were already there. There are indications, certainly, that some of them at least were already in Roumeli before the Greek War of Independence broke out. In 1851, an Arvanitovlach falkari established a summer hut settlement at Voboka on the southern slopes of Othri, near the village of Pelasyia and what was then the frontier. In a conversation with Theodoros Yennaiou Kolokotronis (Theodoros Kolokotronis’s young grandson), the falkari’s aged tselingas, whose name was Poulios, claimed to have been a companion of Konstandis and Theodoros Kolokotronis and a friend of Odysseas Androutsos.[12] This supports Aravandinos’s view that there were Arvanitovlachs in Roumeli long before 1821, and it also, perhaps, bears out what Pouqueville says about the Vlachs from Kossina.

When Henri Belle travelled through almost the whole of what was then Greece between 1861 and 1874, he reports that the total number of Vlachs living in Roumeli, and principally in Akarnania, the Agrafa, and on Iti, was around 12,000.[13] So it is clear that, during the nineteenth century a considerable number of Vlachs, more specifically Arvanitovlachs, were gradually assimilated in towns and villages over almost all of Roumeli, and became an integral part of the population of the new and still tiny Greek state. Even more interesting is Cousinery’s reference in 1831 to the presence of Vlach-speakers, probably Arvanitovlachs, in the area of Argos in the Peloponnese. He reports that, after the War of Independence of 1821, he met some Vlachs, men and women, in Argos market, who told him that they were pastoral nomads with settlements in the mountains around Argos. He also notes that these Vlachs spoke a Latinate language, like the Vlachs he had met in Macedonia.[14]

Certainly, these were not the only Vlach groups which made up the population of Roumeli. If what Pouqueville says even partially reflects the facts, then we must also take into account some other groups of Vlachs, who were already permanently settled in a large number of villages in Roumeli in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. He calls them ‘Bouii’, and they may probably be identified as the Bouii found in earlier writings. He notes that they lived in three discrete groups of settlements, and that a large segment was already at an advanced stage of assimilation. These groups of Vlach settlements were: i) around Ypati on the north-western slopes of Iti;[15] ii) south and south-east of Karpenissi;[16] and iii) probably north of Lamia, on the slopes of Othri, near the Fourka pass.[17] Pouqueville estimated their total number, together with some pastoral nomads of the same provenance, at about 11,000.[18] We may consider that the semi-nomadic inhabitants of the village of Stavropiyi in Evrytania (known as ‘Ablianite Vlachs’, from the old name of the village, Abliani) were descended from them. By the beginning of the twentieth century, the Ablianites appear to have been exclusively Greek-speaking, with no memory of having known or used any other language, though they faithfully observed the transhumant Vlach lifestyle. In the winter, some of them went down to Evinohori at the mouth of the River Evinos near Messolongi, and others to Lamia.[19] However, questions still remain: were these population groups once Vlach-speakers? When did they settle in Roumeli? And what eventually became of them? The most likely answer is that the Arvanitovlachs who were in Roumeli when the Greek state came into being, or shortly afterwards, had no direct or close connection with Pouqueville’s Bouii. The Bouii were probably part of the Vlach population of the Great Vlachia of the Middle Ages. But more exhaustive research is certainly required if these questions are to be answered more clearly.[20]

Page 1 of 2

Subtracts from "The Vlachs: Metropolis and diaspora"

Migratory movements during the 19th century and until 1912

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA VII. The Vlachs in north-western Macedonia 3.3.3. Migratory movements during the 19th century and until 1912 By around the mid-nineteenth century, the network of...

The diaspora and the colonies of the Grammoustian Vlachs

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA VI. The Vlachs of Grammos 2.8.4. The diaspora and the colonies of the Grammoustian Vlachs It is worth mentioning, albeit briefly, the villages and the hut...

Moschopolis, the glory days, 1700–1769

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA V. The Vlachs of Moschopolis and the surrounding area 3.2. Moschopolis, the glory days, 1700–1769 In the eighteenth century, Moschopolis and the local Vlach...

The Arvanitovlachs in Roumeli (Mainland Greece)

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA IV. The Arvanitovlachs 7. The Arvanitovlachs in Roumeli (Mainland Greece) In around 1840, the large Arvanitovlach settlement at Bitsikopoulo was apparently...

The Kupatshari

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA III. The Vlachs of the Northern Pindos: The Vlach villages in the Grevena area 1.3. The Kupatshari Apart from the known Vlach villages, there is another distinct...

The debate about the former extent of Vlahozagoro

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA II. The Vlachs of Zagori and Konitsa 3.2.2. The debate about the former extent of Vlahozagoro According to one out-dated view, the Vlach villages in Zagori were...

The Vlachs of Aspropotamos: The conditions and the agents of development

THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA I. The Vlachs of the Southern Pindos The Vlachs of Aspropotamos and Malakassi 7.1 The conditions and the agents of development The difficult circumstances of the...